Get the lay of the land with the Ag Value Chain

A framework for understanding the major players in agriculture

If you’ve ever ordered a new couch, you understand how the Supply Chain works.

Raw materials like fabric, wood and foam get passed through many hands, each adding value along the way, until the output, a couch, reaches you, the consumer. It’s the magic of a modern, globalized economy — you can sit in your living room, click ‘Buy’ and a couch lands on your doorstep (albeit a few months later).

Think of the Agriculture Value Chain as the Supply Chain dressed up in flannel and cowboy boots — it’s one of the most important mental models to unlock an understanding of agriculture.

While you may go to the grocery store every week, the Ag Value Chain has a lot under the hood that we as normal grocery shoppers simply don’t see. These little secrets will help you better understand why agriculture operates differently than just any old supply chain.

The Ag Value Chain: How it Works

If you buy your food directly from local farmers, you may be thinking that the Ag Value Chain looks something like this:

Now before we decide we’ve got this whole Ag Value Chain thing sorted out, there’s something you should know. Consumers buying directly from farmers is a growing trend, however it’s still a very small portion of the total dollars spent on food — less than 5% in the US.

So how does the other 95% work?

Let’s walk through how corn, soybeans and wheat in the United States flow through the Ag Value Chain to get an idea of all of the different segments along the way. Those three grain crops have a major impact in agriculture because they account for over 60% of the total farmed land in the US alone, and the US has the second most acres of cropland in the world.

To grow a crop, most farmers need at a minimum: land, seed, equipment, labor, fertilizer and in many cases, pesticides. Each of those come from different manufacturing companies who sell directly to farmers or to agricultural retailers who then sell to the farmer. Oftentimes, the retailer provides advice and services on top of the physical products they sell (like when you go to the eye doctor because you need new glasses and then you end up getting an exam and drops for your dry eyes too).

Once the farmer grows and harvests their grain, the crops are sold to grain traders. Farmers may also sell a large chunk of their grain to ethanol processing plants.

Grain traders are colloquially called “the ABCDs” because of the names of the biggest players in that segment (Archer-Daniels-Midland, Bunge, Cargill and Louis Dreyfus), which is also my favorite abbreviation in agriculture. The ABCD’s trade commodities like grain around the world and process grain into food ingredients and animal feed.

And finally, we meet the consumer. Those food ingredients are further processed by consumer packaged goods (CPG) companies into your favorite snacks. The animal feed is fed to livestock which then graces your plate as a hunk of protein. And the ethanol makes it into your gas tank.

Phew! We made it through from inputs to outputs.

Scale and Consolidation: the wonders of the Ag Value Chain

There’s a couple mind-blowing things about this whole Ag Value Chain.

First - these are massive volumes of physical goods that are in many cases moving vast distances. We’re talking over 15 billion bushels of corn in the US per year alone, which if packed into rail cars linked end-to-end would be enough to circle the Earth almost twice 😱 It’s hard to conceptualize the choreography of all of these pieces moving through the real, honest-to-goodness, 3D world. This ain’t the metaverse baby!

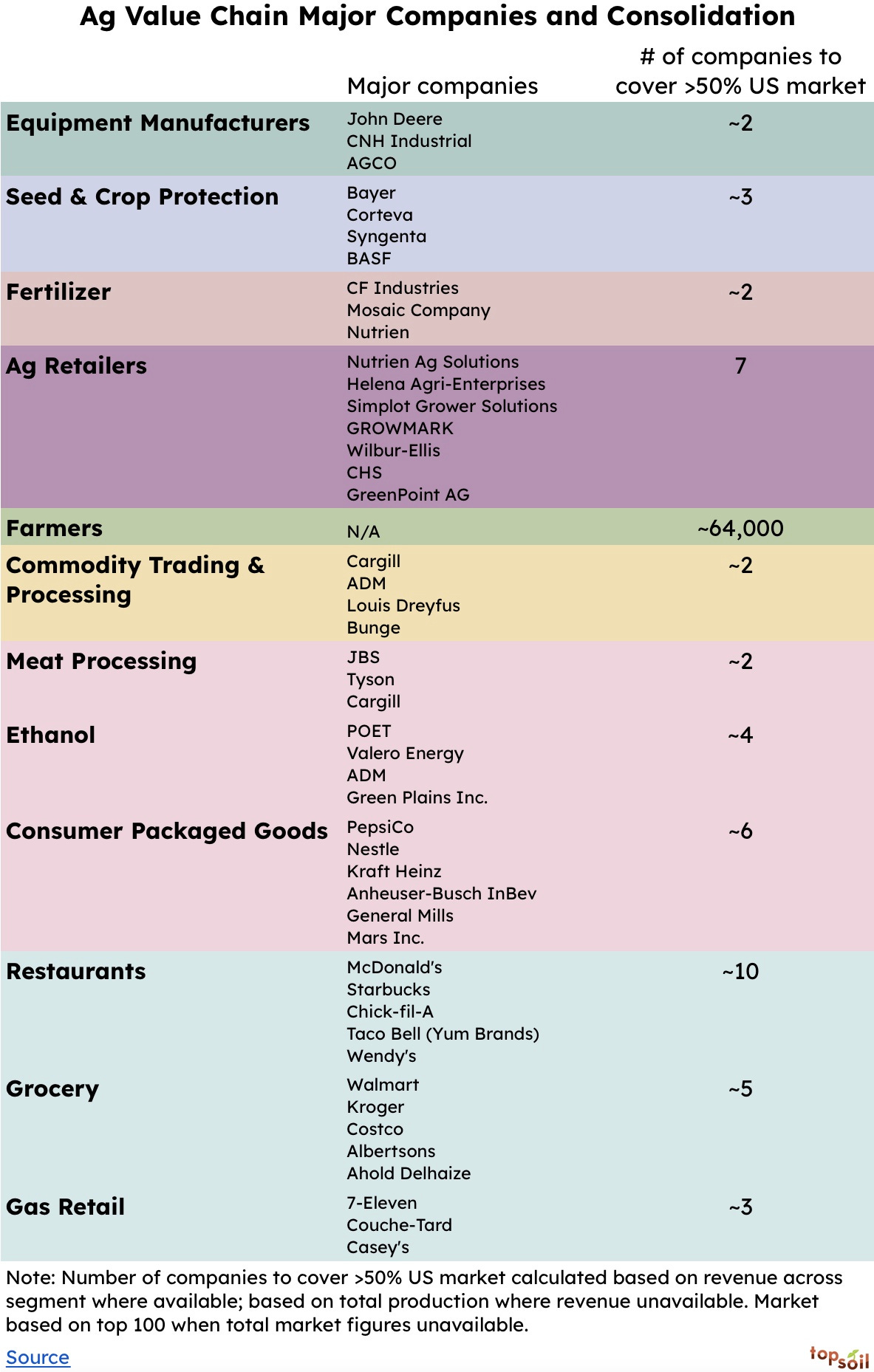

Second - at every step along the way, the Ag Value Chain is incredibly consolidated, meaning that there are fewer and fewer players gobbling up larger and larger slices of the total pie.

Farmers, as a segment, are the least consolidated, but growing more consolidated each year. Similarly, every other segment has become more consolidated as companies have merged or bought up competitors. Like a whirlwind season of Love is Blind, seed companies have been rapidly pairing off and saying “I do.” Dow Agriscience and DuPont merged into Corteva Agriscience, while Monsanto became one with Bayer, creating two of the top 3 largest seed and crop protection companies in the past 5 years alone.

So why does consolidation matter in agriculture?

One consequence of consolidation is there’s less competition.

Imagine you are a farmer buying seed for next year. While each of the major 3 seed companies carry many brands, there’s only a handful of companies to choose from. Good luck!

True, this isn’t exactly what your economics professor would define as a monopoly (there’s technically more than one seller). And very true that the existing biggies are working day in and day out to beat out “the other guys.” The fact remains, however, that with fewer competitors in a given segment there’s often less choice for buyers.

On the flip side, consolidation is excellent for scaling efficient production.

When the Ag Value Chain is working well, it produces a miracle of abundant, affordable and safe food. Compare the amount of resources someone in 2022 spends on food to someone in 1800, or even further back to 400BC.

We can thank the Ag Value Chain for the fact that you and I and millions of others around the globe don’t have to spend the majority of our daylight hours to find something to eat.

However, the consolidation that makes the Ag Value Chain mighty also makes it more brittle.

Any disruption — like the pandemic that wreaked havoc across the Ag Value Chain, and the Russian-Ukraine war, and now the historic drought of the Mississippi River slowing trade on a critical artery — can have a brutal domino effect if only a few key players or regions are impacted.

The Ag Value Chain of the future

All of the above applies to a US-centric grain-focused snapshot of the Ag Value Chain today. Yet as the old adage goes, “the only constant is change.” We’re at an incredibly exciting time in agriculture where it feels like change is both urgent and possible.

In particular, there are three factors driving change in the Ag Value Chain by blurring lines between segments and and creating completely new categories and winners:

New technology allowing players in the value chain to deliver better on age-old needs. John Deere is an A+ example of a company that has invested heavily into digital technology to make their equipment even more valuable to farmers. With their recent launch of AI-enabled See and Spray, it’s clear that John Deere is putting pressure on crop protection companies by helping farmers spray less for the same result.

Business models built around cross-value chain collaboration. With improved traceability and visibility beyond the walls of any given company (hello Information Age), there are more opportunities for companies to partner with others who are further upstream or downstream. For example, Corteva developed a special variety of soybean that yields high oleic (monounsaturated) oil. Corteva formed a partnership with Bunge, so Bunge would purchase the high oleic soybeans from farmers at a higher price, process the soybeans, and sell the high oleic oil to CPG companies looking to replace the trans fats in their food products.

Climate change resilience. Since agriculture is at the mercy of weather and weather is becoming increasingly unpredictable, we can anticipate (and cross our fingers for) more dollars flowing to make the Ag Value Chain more resilient.

I’d love to hear from you – what do you think the Ag Value Chain of the future will look like?

This is great. Loving your recent articles!

Ariel, thanks so much for writing this. As someone who transitioned into this with no food/ag background, I wish I had this on day 1.