Hello and welcome the 9th edition of Topsoil – a monthly newsletter with frameworks to help you make sense of agriculture, at just the right depth.

Before we get into the weeds today, I want to welcome new subscribers 👋 and share a podcast appearance from last month.

I joined the ever-hilarious-and-insightful Nuss brothers on the Modern Acre Podcast to talk about Sustainability in Agriculture. Feel free to check out that episode, or take a listen to another fascinating deep dive they did recently on the Climate Corporation that I greatly enjoyed.

Thank you for your continued support in reading, subscribing and sharing!

In a tale as old as time, weeds are the villain of agriculture.

Meanwhile, herbicides, one of the major ways of controlling weeds today, are also becoming vilified.

Depending on which corner of the internet you’re scrolling, in this weeds vs. herbicides battle of the baddies, no one wins and our choice is to either starve or be poisoned. Is there a (less depressing) path forward?

I like to think the answer is a resounding yes. Not only that, weed control is the proving ground for some of the most exciting new approaches and technologies in agriculture.

Let’s dig in!

Weeds: A real problem

Weeds are simply plants growing where they are not wanted. And these unwanted plants have a real impact on farmers’ bottom lines.

Weeds harm crops in two main ways. First, weeds can rob the crop of water, sunlight and nutrients, leading to yield losses. If left untreated, these losses can be significant – up to a bushel or more per day of lost yield in studies of corn in the US Midwest. In today’s prices, that’s a little under $5/acre per day. With the profit margin for corn being around $70 for the whole year, this is a serious hit on the farm’s ability to be profitable.

Second, plants take no prisoners when it comes to competing for resources. Some weeds are allelopathic, meaning they release chemicals that harm the crop. If you’ve ever strolled under walnut or eucalyptus trees and noticed that other plants struggle to grow underneath, you’ve seen allelopathy at work. There are 240 such documented weed species, including common weeds like redroot pigweed and lambsquarters.

Finally, beyond the yield hit, the presence of weeds can make harvesting more difficult and can contaminate the harvested product (especially certain types of grain). Contaminated product means a lower quality grade means a smaller paycheck for farmers.

The solution today

So how do farmers address weeds today?

The table below shows some of the main categories of weed control available with a handful of specific examples:

Farmers will often use multiple methods together – called integrated weed management – to reduce overreliance on any one tool and improve overall weed control. The idea is to create conditions where the crop thrives and can outcompete other unwanted plants. As one organic vegetable farmer in California I spoke with recently told me, “None of these practices alone will do everything. But when you start adding them together, then you get a program that works.”

While farmers take action to control weeds in the current season, they also play the long game. Choices made in one year impact weed pressure in future years.

Anytime a weed “goes to seed” or reproduces, more seeds are added to the “weed seed bank” (real term used to describe the weed seeds scattered throughout the soil of a field).

A single weed, like the dreaded Palmer amaranth, can release well over 250,000 seeds, with some estimates closer to a million seeds per plant! Many weeds evolved seeds that work like ticking time bombs, patiently waiting years before sprouting. Other weed seeds germinate throughout the season so a few are likely to slip through the cracks. You can see how even a few escaped weeds can result in headaches for years to come.

These activities cost farmers time and money. Depending on the crop and specific practices, farmers spend anywhere between 5% to 15% of their operating costs on weed management (and often much higher for crops that require extensive hand weeding).

Herbicides: cost effective and controversial

Herbicides, called “crop protection products” in industry-speak (along with fungicides, insecticides and other -cides), are arguably the most important tool in many farmers’ weed management programs. As US Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack stated, "Weed control in major crops is almost entirely accomplished with herbicides today."

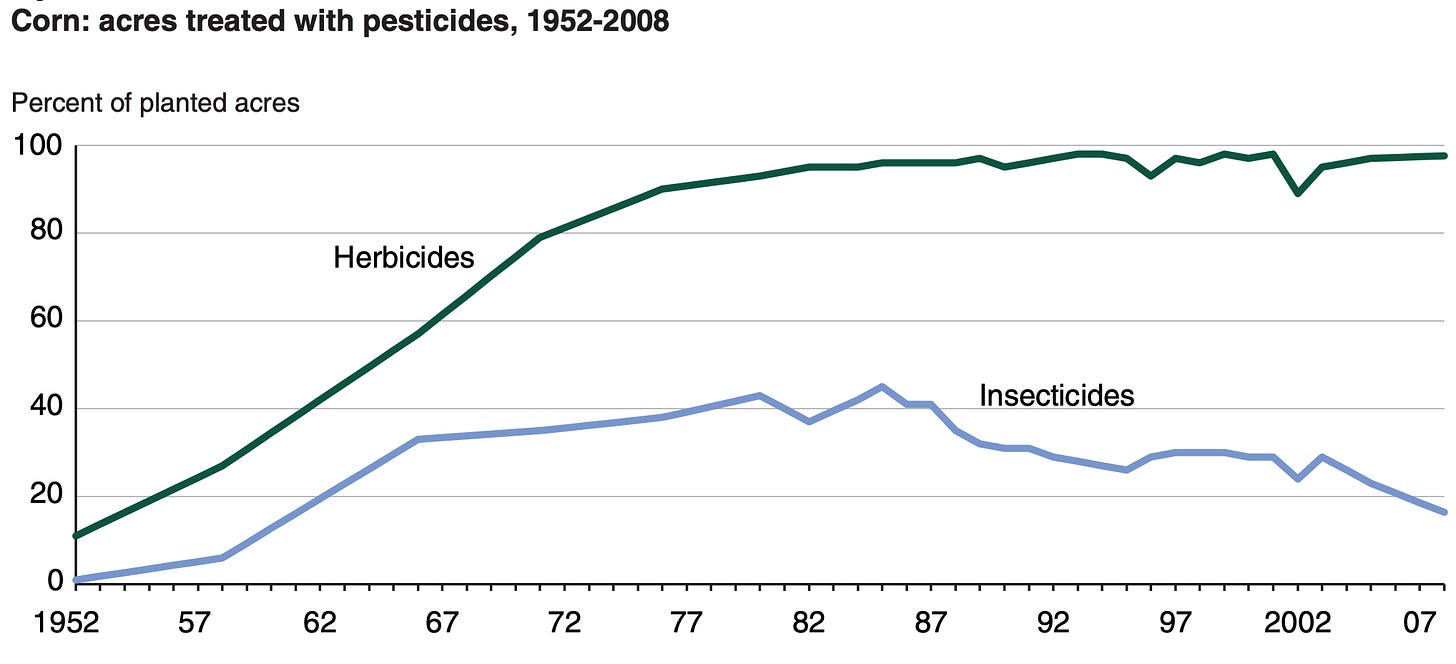

Over the past several decades the costs of labor and fuel have increased. Because herbicides save labor and are relatively cost effective, they have grown in popularity. There are some environmental benefits as well: farmers have substituted herbicides instead of heavy tillage that leads to erosion and release of carbon into the atmosphere.

For these reasons, by the early 1990’s, roughly 98% of corn and soybean acres in the US are treated with at least one herbicide:

And yet, herbicides have downsides.

Risks to human health: Certain herbicides may carry health risks for the people applying the herbicide, surrounding communities, and consumers through residues. There are studies that link exposure to herbicides with cancer, neurodegenerative and metabolic disease, developmental harm, respiratory disorders, and reproductive issues. Harm to human health is heavily dependent on level of exposure: how much someone is exposed to and for how long.

Environmental risks: Certain herbicides can leach into groundwater, runoff into waterways, or volatilize into the air. In these cases, at a high enough concentration, this may cause unintended harm to wildlife or other crops, decrease biodiversity, and contaminate drinking water.

Herbicide resistance: Active ingredients become less effective at controlling certain weeds over time. Some weeds might survive an herbicide application and reproduce. The next generations of weeds evolve to become more resistant to that herbicide over time. Currently, there are 269 recorded herbicide resistant weed species around the world. This has a few implications: farmers must apply more in order to get the same or worse results (“the pesticide treadmill”), different chemistries are needed, and some weeds must simply be controlled by other, non-chemical means.

The bottom line: herbicides are an important tool for farmers to control weeds, with risks that need to be managed. Similar to other activities like driving a car, getting Botox, using power tools, or drinking a beer (hopefully not all at the same time) – there are risks to ourselves and others just as there are benefits.

In order to manage these risks today, there are a few main approaches:

Regulation: In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is responsible for evaluating the risks to human health and the environment of every herbicide, and then approving the “registration” of that herbicide before it can be sold. The EPA must find a "reasonable certainty of no harm" before an herbicide can be used on food or animal feed. Some states have their own regulatory agencies with additional rules. Outside of the US, each country has its own laws governing herbicide use, with the European Union’s rules being some of the most strict.

Label instructions: Each herbicide comes with a label that spells out how to use the product safely and effectively. Labels are serious business – most manufacturers’ warranties will not cover off-label use and it’s a federal offense to use an herbicide without following the label.

Trend towards reduced toxicity: Over the past 25 years in the US, the toxicity of the chemicals used is on the decline, even as the total volumes used may be higher. This might sound contradictory. Basically, not all herbicides are created equal in terms of how toxic they are – some are more toxic and some are less toxic. Some of the more highly toxic pesticides have been discontinued and new, less toxic products are developed, all of which adds up to lower toxicity overall.

Integrated weed management approaches: As mentioned above, other non-chemical approaches are used to slow herbicide resistance and reduce dependency on herbicides alone.

These measures to minimize risks are important, but imperfect. For one, typically the company seeking registration provides the data to the EPA. You see where this is going – that can create an obvious conflict of interest, where industry-funded studies end up being more favorable to the company.

For example, across studies of atrazine, the second most popular herbicide in corn applied on over 50 million acres in the US, the best predictor of whether the study found negative effects or not was funding source.

Even once herbicides are registered with clear, serious-business labels, some estimate that up to 40% of herbicides are applied off-label (meaning the instructions designed to minimize risk are not followed).

Weeds: the once and future proving ground for new tech

The status quo of weed control today feels unsatisfactory. To greatly oversimplify – consumers are demanding affordable food with less pesticides used; communities would like more assurance that their water and environment aren’t contaminated; farmers must produce a profitable crop without taking a yield hit. As a result, innovators are jumping into the fray to find better solutions.

Once before, weed control has been the proving ground for technology that reshaped the agriculture industry. In 1996, Monsanto began selling the first genetically modified soybean seed. This new seed offered something that had never been done before – the crop was tolerant to the herbicide glyphosate. Instead of multiple tillage passes or spraying several other selective herbicides, farmers could now spray their entire field once and wipe out all the weeds. It was an immediate blockbuster because it made weed control massively easier.

After this watershed event, chemical companies like Dupont, Dow, Monsanto and Syngenta went on a buying bonanza, gobbling up seed companies to form the modern-day agriculture input giants.

Today, we might just be on the cusp of another shift.

Weed control makes sense as a starting point for new technologies in agriculture. Billions of dollars are on the table because weed management is a consistent, global problem ($20B globally each year, to be precise). Unlike harvesting, weed control does not require nearly the same amount of precision and accuracy to still be valuable.

Given these conditions, weed control is a fantastic proving ground to see which technologies will have real promise over the next decade in making farming more sustainable and profitable. A few technologies that are under development:

Targeting weeds with precision: Computer vision using artificial intelligence, automation, and in some cases, drones, are coming together to help farmers precisely target the offending weed and leave everything else alone. Beyond the highly publicized See & Spray system from John Deere, there are dozens of other companies tackling this same challenge across many crops.

Diversifying types of weed control: Last week at the FIRA agriculture robotics conference in Salinas, CA, a panelist summed this up nicely, “You can pull ‘em, zap ‘em, shoot ‘em. You can do anything to a weed these days!” Beyond some of the precision spraying solutions entering the market, he was referring to several other options that allow farmers to precisely till weeds between the crop or even incinerate weeds with a laser beam.

Emerging biologicals: Bio-based herbicides have active ingredients sourced from minerals, microbes, or biochemicals (sometimes based on allelopathy described above). Efficacy and ease of use are still major hurdles to overcome as Sarah Nolet explains, however, the biologicals market is anticipated to grow at nearly 14% each year for the next 5 years, with biopesticides being a part of that growth.

Before we ascend into frothy fantasies of hordes of unmanned robots sharpshooting weeds with benign biologicals, we have to keep in mind a simple fact. Any new technology in agriculture must actually deliver a real benefit (like cost savings, less risk, or greater efficiency) with a winning business model to become successfully adopted on the farm.

We’ve seen it happen once before in the past 30 years – perhaps the next industry shaping technology will again emerge from the weeds.

Topsoil is handcrafted just for you by Ariel Patton. Complete sources can be found here. All views expressed and any errors in this newsletter are my own.

How did you feel about this monthly edition of Topsoil? Click below to let me know!

Weeds is certainly a problem, but I believe that for tropical agriculture, the main problem today are pests. In soybeans for example, stink bugs is the major threat. The insecticides are becoming inneficient and the control of insects is very harmful for the environment.

You do not promote agriculture. You promote agrabusiness. Sad