One size does not fit all when it comes to crops

A framework for understanding the major crops in agriculture

I hope your 2023 is off to a healthy and productive start! I’m thrilled to see many new faces here on Topsoil – a monthly newsletter with frameworks to help you make sense of agriculture, at just the right depth.

Today we’ll be covering the deliciously diverse spectrum of crops and how that shapes farmers’ decisions and the agribusinesses that serve them.

Thank you for reading, subscribing and sharing!

There are 369,000 known species of plants on Earth.

Of those, 2,500 are domesticated to some degree by humans — bred to produce food, medicine, fiber or to beautify homes and gardens.

Today, we grow about 170 crops around the world on a commercial scale. And while we’re playing this game, only three crops (rice, corn and wheat) provide 40-60% of the calories for the entire world’s population.

While three, or even 170, species doesn’t sound like a very big number for all eight billion of us humans to rely on, it still represents a stunning amount of diversity when you consider how each crop is grown.

Plant moms everywhere will understand that just like one houseplant will need more sunlight or less water than another, each crop is farmed differently and requires different tools, techniques and environments.

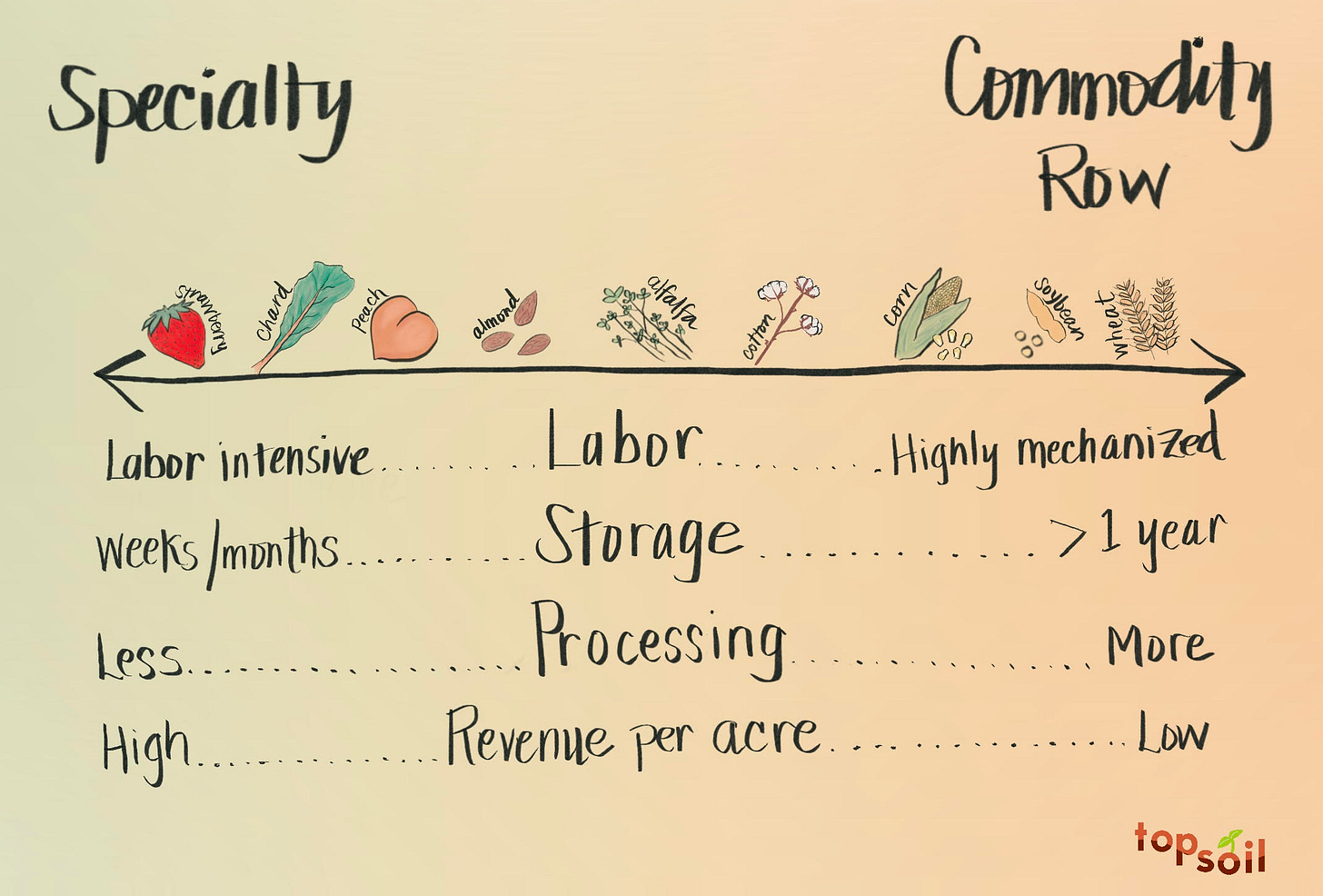

Introducing the Crop Spectrum

While each crop is unique, some are more alike than others. One helpful way to make sense of the major crops in agriculture is to think of them on a spectrum. Getting to know this spectrum is critical to understand the decisions a farmer makes. There’s a reason why the first question farmers are often asked is, “what do you grow?”

The spectrum also reveals one of the biggest challenges for ag businesses and ag policy makers – farms are as diverse as the crops that they grow, so no solution can be one-size-fits-all.

On one end of the spectrum, we have specialty crops: fruits, vegetables and nuts. At the other end of the spectrum we have commodity row crops: grains like wheat or corn and oil seeds like canola and soybeans. In between are various field crops like tobacco and cotton that share some characteristics from either end but don’t fit cleanly in either category.

Across the spectrum, crops vary across a few key characteristics.

Labor: Most specialty crops, like strawberries, kale and peaches are picked by hand. The human “hardware” that has evolved over tens of thousands of years to spot ripe fruit or a mature leaf of kale and delicately pick it without damaging the tree or plant still outperforms machines (though there are some neat robotics companies tackling this challenge).

Whereas specialty crops rely heavily on teams of people, commodity row crops rely heavily on mechanization (aka big ass tractors). Commodity row crops are typically grown on a much larger scale, making automation a must to plant and harvest those acres. Equipment is a major expense for commodity row crop farmers – a combine harvester for grain can easily cost over one million dollars.

Storage: Like the sad looking parsley in my fridge, many fresh fruits and vegetables have a relatively short shelf life — in many cases they require refrigeration and will spoil within weeks or months. Of course, some specialty crops (like nuts) can be stored for longer than leafy greens and fruit, but even so, commodity row crops are much easier to store for well over a year.

This storage factor impacts how farmers can sell their crops. Often, specialty crops that are destined to be eaten fresh (like romaine lettuce) are sold in “spot markets,” where a produce wholesale buyer will buy the produce for immediate delivery.

Beyond spot markets, many commodity row crops can also be sold in “futures markets,” where the price is locked in with an agreement to deliver the grain at a date in the future. Commodity futures markets tend to have many more buyers and sellers with prices changing every day, similar to the stock market.

Processing: As we walked through in the Ag Value Chain for grain, commodity row crops must pass through many hands and stages of processing to become something that you and I would recognize in our kitchens. Specialty crops are either grown for fresh markets (like you see in the produce aisle) or for processing (like you find in the frozen or canned goods aisles). In either case, typically there is less processing required before the crop reaches the consumer which influences what a farmer prioritizes.

I have yet to meet a farmer who doesn’t care about the quality of the crop that they grow, whether it’s soybeans or dates. However, for farmers who grow specialty crops for discerning consumers at the grocery store, the crop’s aesthetic appeal is extra important and can make or break payout at harvest time.

Revenue per acre: This brings us to one of the most interesting aspects of the crop spectrum – the money.

The table below shows a selection of crops from across the spectrum. Specialty crops are colored in green. Commodity row crops don’t have a firm definition from the USDA, so I colored everything that isn’t a specialty crop in orange.

Reading the table, your first reaction might be “why doesn’t every farmer just grow specialty crops?”

Or more directly “should I stop what I am doing and start growing strawberries?”

While it’s true that specialty crops command more revenue per acre, that may not always translate into more profit per acre given the high cost of labor and land where specialty crops can grow. The average price of farmland in California (the state that produces the most specialty crops) is over $20k/acre compared to $11k/acre in Iowa (the state that produces the most corn). This helps explain why vertical farming start-ups have heavily focused on growing specialty crops – the economics seem much brighter than attempting to grow other commodity row crops indoors.

Overall, the specialty crop market is relatively small when compared to the other crops produced. In 2017 in the US, farmers produced around $41 billion dollars worth of fruits, vegetables and nuts, which is smaller than the corn grain production value alone ($51 billion).

Beyond profitability, farmers have many factors like those above to consider if they decide to add or change crops. This complexity is one reason why over the past few decades in the US there is a trend of farms growing fewer different types of crops: 2 to 3 crops on average today instead of 4 to 6 crops previously.

This leads us to a catch-22 that many AgTech companies face.

They can create products for low-revenue-per-acre but high acreage commodity crops, fighting hard for very tight wallet share. Or, they can serve high-revenue-per-acre specialty crops but risk creating solutions that are only applicable to small slices of the market. Companies often make this choice early on. One example is Verdant Robotics who recently raised nearly $50 million dollars to focus on weeding specialty crops, starting with carrots.

The crop spectrum is one of many spectrums in agriculture

Despite public perception of farmers being one big overalls-wearing bloc, there’s huge variation among farms based on other dimensions beyond the crops they choose to grow, such as:

geographic region (this analysis has been very US focused and other regions may operate differently),

whether a farm raises livestock,

whether crops are annual or perennial,

agronomic practices like tillage or rotations, and

even within a single crop, selection of varieties or end uses (both sweet corn for summer grilling and corn grain that becomes ethanol are different varieties of one plant).

We’ll cover more of these dimensions in future editions of Topsoil. Thank you for reading!

Very interesting and enlightening!

Fascinating analysis! It's incredible to see the amount of variety we have before we even start getting into hybrids, subspecies and the like. While corn shows up as one row in your table, the reality is that deciding to plant corn opens you up for thousands of options of seed you can choose. The complexity is really humbling, thank you for helping to simplify some of it =)