Turns out, Seasons are a Thing in Agriculture

A framework for understanding seasonal activities in agriculture

What I’m about to say may sound very, very obvious to many folks reading.

I’m going to say it anyway because it is something that can be so easily overlooked. And once overlooked, can lead to some pretty embarrassing marketing or ineffective product launches. Or, you know, a whole year of missed opportunity.

Seasons are kind of a big deal in agriculture

Seasons are one reason why things operate a little differently in agriculture: activities are cyclical, feedback loops are longer, and certain business models simply don’t fly.

Seasons are the steady drumbeat of the agricultural calendar. Because the main agricultural activities happen outdoors (we’ll save vertical farming for another day), weather determines what can actually get done in the field throughout the year.

Borrowing a term from biology, a “critical window” is a period of time when an organism is developing and needs certain experiences and inputs to develop normally — more so than at any other point in its life.

In agriculture, seasons indicate critical windows. If something doesn’t get done in this time period, poof! The whole year can be a bust.

For that reason, farmers are highly attuned to these critical windows for their crops. As soon as a season begins, they don’t waste time and will work non-stop until the job is complete because there are very real consequences to the bottom line if they miss the critical window.

The four major seasons in farming

You’ve heard of Tax Season, Allergy Season, Back-to-School Season, and Pumpkin Spice Season. Each of these entails a change in the weather and frenzy of corresponding activity — whether that’s frantically digging up receipts from last year or mainlining pumpkin spice lattes.

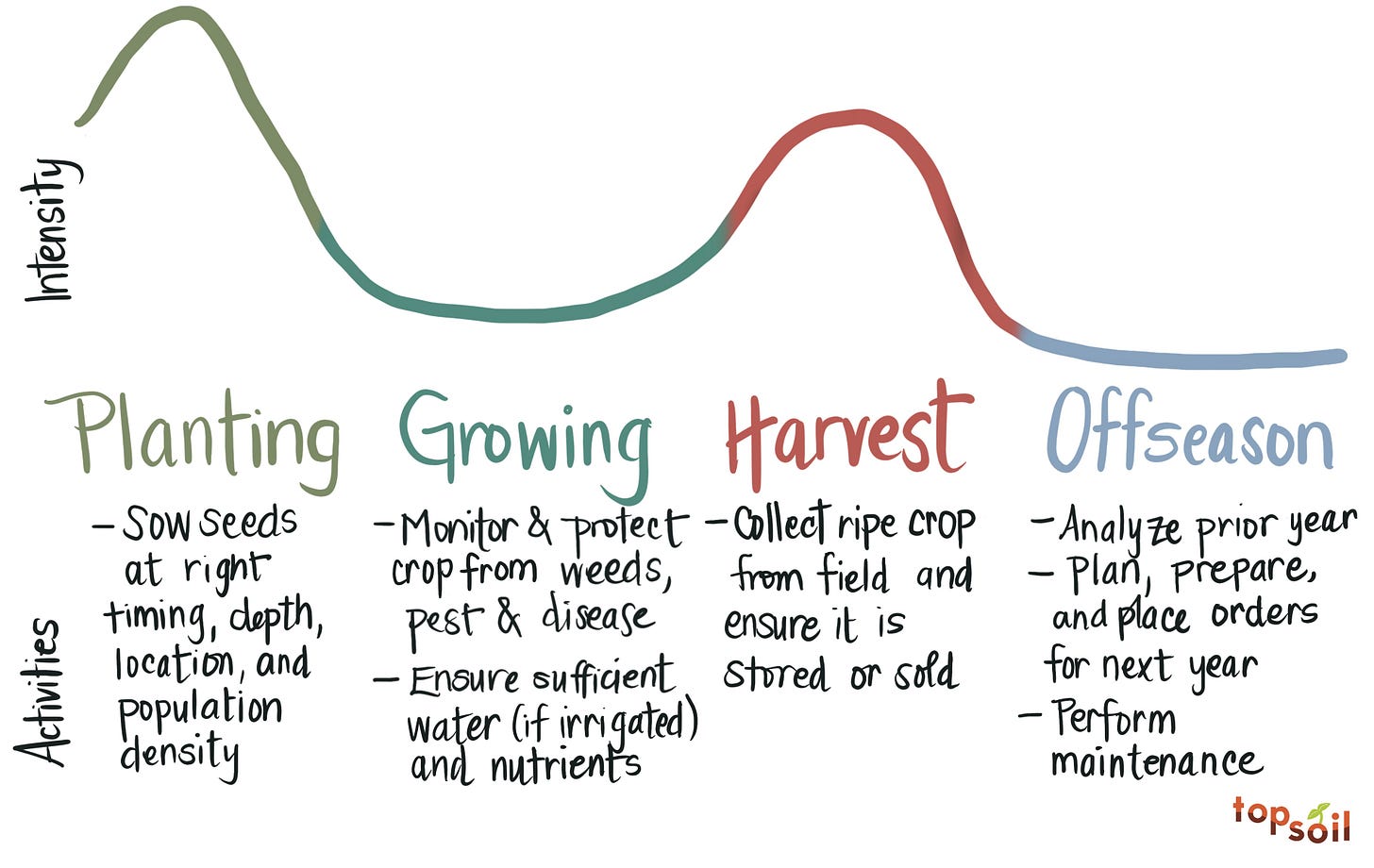

Similarly, for many annual commodity row crops, we have the Planting Season, Growing Season, Harvest Season, and the Offseason. Let’s walk through the year with a crop like corn or soybeans in mind.

As you might imagine, the key thing that happens during the Planting Season is that specially selected seeds are sown in the ground at the right time, location, and population density.

Before farmers can get to planting, there is often work to prepare the ground and make it as welcoming as possible for each tiny seed: fertilizing, spraying herbicide to prevent weeds from competing with the crop, tillage, or terminating a cover crop before the new crop is planted.

Once the field is prepared, the ground is suitably warm, and weather permits, planting equipment (often GPS guided) is used to precisely plant each seed in the ground at the appropriate depth. Planting Season is typically the most intense season because the rest of the year depends on a successful planting and every day matters.

Just how much is each day worth?

Studies that compared the planting date and resulting yield in soybeans in Iowa found that after conditions were suitable for planting, each day late led to a yield loss of up to 1% per day. When there are so many other factors that can also chip away at yield, every percent matters.

Once the seed is in the ground, the soybean or corn plants will typically emerge within a couple of weeks depending on temperature. Farmers check to see if the planted seeds actually emerge, and if not, make a decision to re-plant certain areas that didn’t sprout (“had poor emergence” in agronomy-speak).

Now, in the Growing Season, the farmer and their team do everything in their power to protect the crop and nurture it to reach its full yield potential.

Farmers and members of their farm team will “scout” fields during the Growing Season keeping an eye out for problematic weeds, pests, signs of disease or nutrient deficiencies or irrigation issues. This entails driving out and walking around the field, and in many cases using tech like satellite imagery or drones to get eyes on every acre on a regular basis.

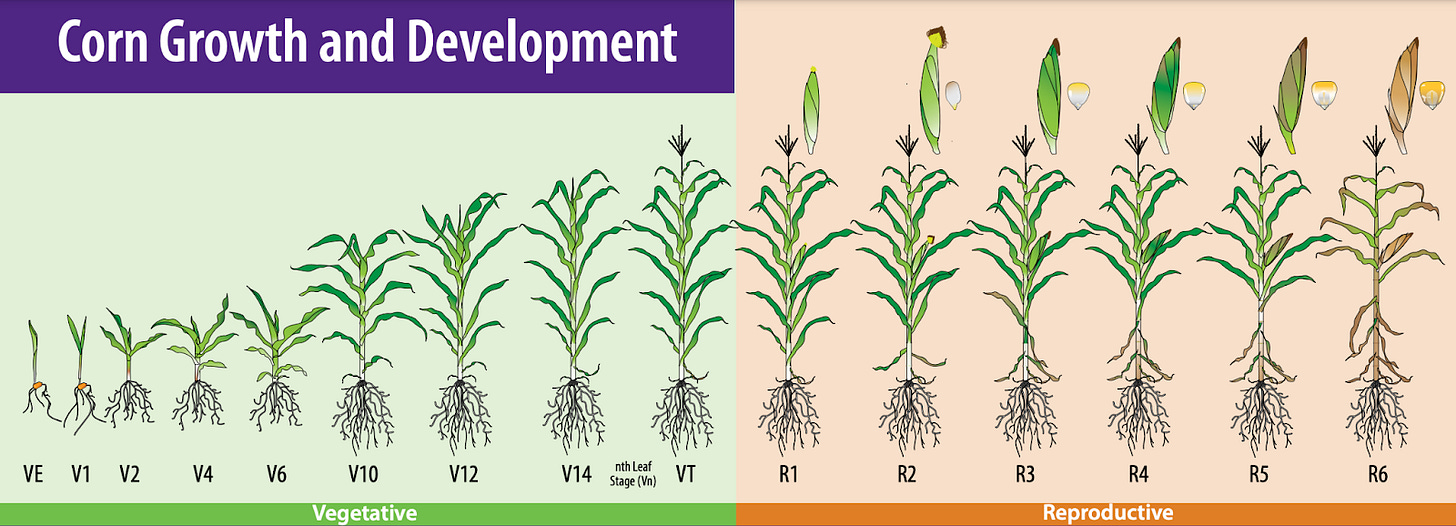

Farmers and agronomists keep tabs on the crop’s development through recognizable growth stages (an example of corn’s growth stages below). As the weeks roll forward, the crops begin to develop the grain that will be harvested. Once the crop reaches maturity (R6 in the chart below for corn), farmers monitor the moisture of the grain to decide when to begin harvesting.

Commodity row crops like corn and soybeans are harvested with massive combine harvesters — essentially little factories on wheels. The combine cuts the entire stalk of corn and pulls it inside, where it separates and holds the grain while spitting out the rest of the plant material — all at the speed of 70 corn plants per second. On a good day, a combine can cover 150 acres (the size of about 27 city blocks in Manhattan).

These are the mesmerizing videos you’ve probably seen of a giant tractor rolling across a field and sweeping up rows and rows of dried crops (and if you haven’t seen what this looks like, or how the inside of a combine is about as high-tech as the inside of a spaceship, I highly recommend checking out some videos!).

Finally, we get to the Offseason. The time for farmers to get caught up on maintenance, meetings, and me time. During this time, farmers are fixing up equipment, making purchases for the upcoming year, securing financing, addressing field fertility and drainage issues, spending time on bigger improvements around the farm, and hopefully if the prior year went well, taking some well-deserved vacation.

Seasons vary by crop and are local by nature

Seasons are another case where one-size doesn’t fit all when it comes to different crops. Take almonds for example. As a perennial crop, planting does not happen every year and there are other critical windows (like bloom) where certain activities must happen, like setting out beehives for pollination. Another example is alfalfa, which is planted only every 3-7 years, but is harvested multiple times a year.

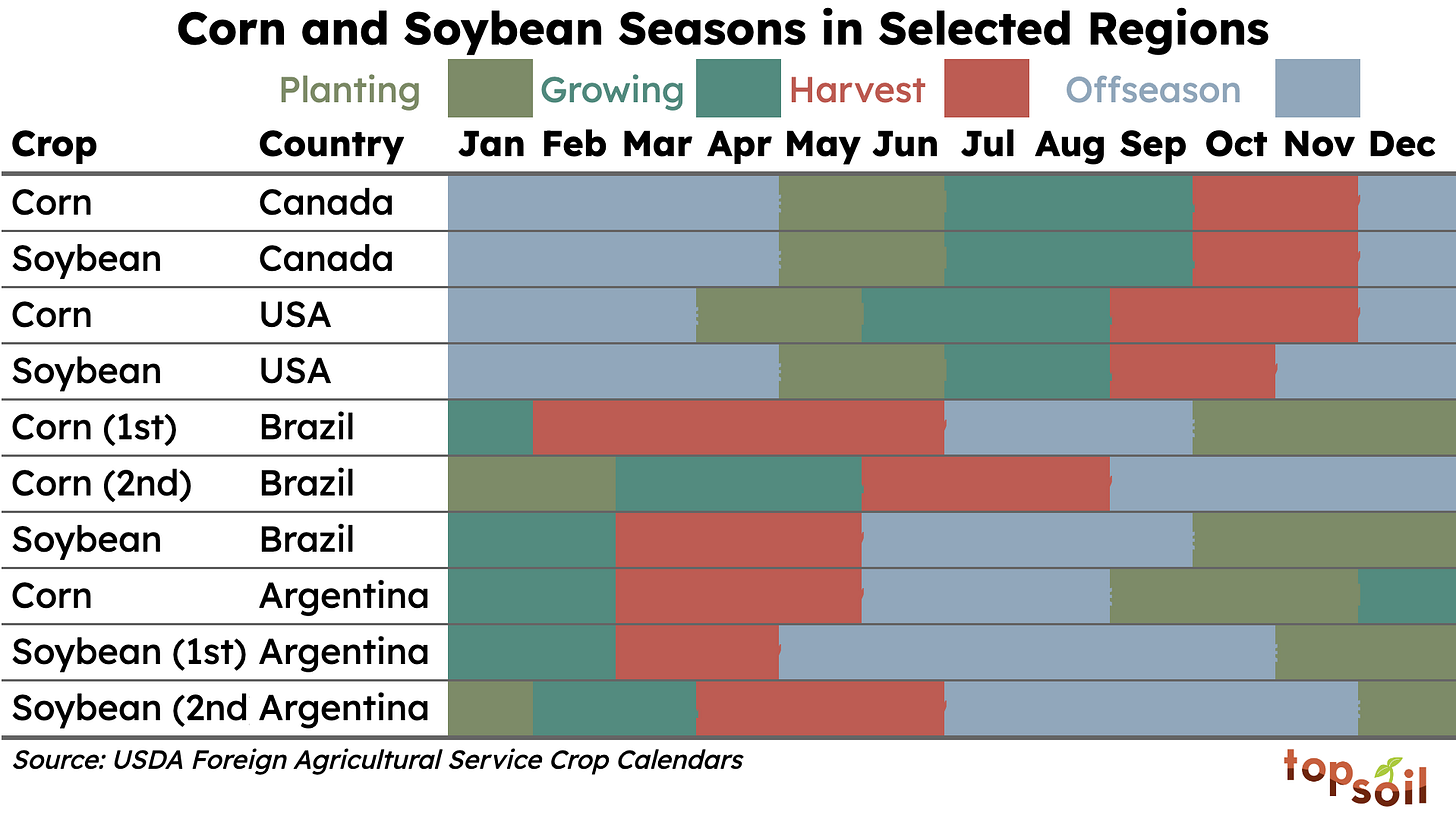

Seasons can also look different depending on where in the world you farm, which makes sense because different parts of the world have different weather. For example, Brazil is known for having not one, but two, corn crops in the same calendar year. The second "Safrinha" corn crop accounts for about 70% of Brazil’s total corn production.

From this chart, you will notice that within a region, each season often starts in the south and moves north. In the US for example, Texas may be planting corn as early as February while Minnesota may not start until April.

Seasons make for longer feedback loops in agriculture

There’s a phrase in agriculture, “A farmer has 40 chances.” Because of the seasonal nature of agriculture, farmers get one “chance” per year over their career to try new things, whether that is a new crop variety, new equipment, or cropping practices. They can then implement those learnings into the next year. Because of the seasonal nature of farming, each feedback loop takes a year.

This is in sharp contrast to how a lot of the software world runs, where the focus is agile development and rapid iteration – launching new things, getting feedback near-instantaneously, making changes, and launching newer, improved versions in short quick cycles. If a software team is launching every two weeks, that creates 26 feedback loops and opportunities to improve each year, instead of the one opportunity each year in farming.

Some of the most successful AgTech companies have recognized this tension and developed approaches to minimize the risk to farmers while maintaining a shorter-than-once-a-year feedback loop. For example, Sound Agriculture provides a guarantee to refund farmers who don’t experience positive ROI when they try Sound’s product, so that farmers can try something new risk-free, while Sound can continuously update their formula throughout the year for better performance.

Why we haven’t seen the Uber of Ag be uber successful

As my husband and I drive through the Central Valley of California any time of the year outside of tomato harvest season, we pass by yards full of dozens upon dozens of empty, parked tomato trucks. My husband, who is an accountant, always ruefully remarks, “look at all those depreciating fixed assets!” (Accounting jokes amirite)

Like wings on Super Bowl Sunday, everyone has the same critical window where they need the same equipment all at the same time. For this reason, farmers must have a large amount of fixed assets like heavy equipment laying around for the majority of the year, going unused. It is simply too costly to not have the equipment available when it is needed during the critical windows. Thus, the sea of tomato trucks depreciating before our eyes.

Unlike the Ubers and AirBnBs of the world where unused fixed assets like idle cars and empty vacation homes have become the fodder for booming new business models, this hasn’t worked yet in agriculture because of seasons – a simple reality that creates massive complexity.

Topsoil is handcrafted just for you by Ariel Patton. All views expressed in this newsletter are my own. Complete sources can be found here.

Excellent analysis as always, Ariel! Your comments about the depreciating fixed assets reminded me a lot of how farming assets are used in different ways around the world.

For instance, in North America, it's not uncommon for a single farming operation to own an entire fleet of agricultural machinery (tractors, sprayers, combines, etc). The situation is very different in places like the Indian subcontinent or Africa, where plots are tiny in size and whole communities share the ownership, maintenance, and usage rights of a single tractor (which is many times smaller than a typical tractor in the USA, for instance).

One of the companies I love following is Hello Tractor, an African startup revolving around tractor-sharing powered by technology. Societal and infrastructure constraints power innovative business models around the world :)

Thanks, really interesting!

I think one of the biggest challenges in the ag-tech world, is being useful the whole year, overcoming the seasonality of the business.

How do you see it evolving? What needs the farmers have in the off-season, and are not answered yet?

There is a lot of focus on the in-season - drones/scouting/satellites, etc.