If you thought that the most exciting things to happen in the United States in February were the Super Bowl or Valentine’s Day, you would be wrong.

In fact, the hottest thing to drop this month was the 2022 Farm Census from the US Department of Agriculture. This once-in-every-five-years report is chock full of data from America’s nearly 2 million farms.

So what does this 757 page long beach read actually tell us?

Today we are going to look at key trends from the Census. While we’re at it, we’ll also challenge some of the age-old narratives about US farms. Let’s dig in!

America’s farmers are getting older

In 2022, the average age of the American farmer was a little over 58.

Back in 2017, it was 57-and-a-half.

See? A 0.6 year difference. *Dusts off hands* enough said about that!

Just kidding – of course we’re not stopping there! Let’s look at the number of farmers by age group to better understand what is going on here:

The total number of producers stayed relatively flat, around 3.4 million total producers in 2022.

We see that the biggest drop-off was among the 45 to 54 year-olds. What the heck happened to them?

One hypothesis is that the 45 to 54 year-old cohort was discouraged from farming in the first place because of the 1980’s Farm Crisis. As a twenty-something looking for a job in the late 1980’s, farms were in significant distress and farming likely did not seem like a plausible career path.

I’d love to hear from others (especially those who may have lived through this) as to what else might be the driver for this drop-off.

Why does the average age of the American farmer even matter? As Sarah Nolet describes, oftentimes this statistic is trotted out to lazily imply that farmers won’t adopt technology, which is not necessarily true.

Looking at the chart above, we see an increase in the farmers who are 65 and older. With farmers getting older and eventually retiring (yes – even those granddads still driving a tractor at 83!), one real consequence is that there will likely be many farms and farmland that change hands over the next decade.

This has many possible effects:

there is a greater need for succession planning on farms,

there are potentially new opportunities for younger farmers (and the need to ensure that they have the knowledge, skills, and abilities to succeed),

we may see further acceleration of farmland consolidation into fewer hands.

The vast majority of farms are still family-owned

As we think about the potential of farms changing hands in the next decade, it’s important to understand who owns farms in the US today.

Read enough food packages or media headlines and you’ll see a common story that goes something like this: “There are two kinds of farms:

Giant evil corporate monoculture farms churning the soil into chalky dust to produce empty calories

Small wholesome family farms growing two heirloom zucchinis, three pigs, and a horse with a red barn”

The reality is, fortunately, much more nuanced. From the data, we know that the vast majority of farms in the US are family-owned.

The 95% of family farms can be small or large – some don’t break even, and many (over 9,000 farms to be exact) make more than $5M in annual sales.

Some are owned by one person, and many are organized into complex legal structures so more family members can own part of the farm (legally a partnership or corporation). Regardless, at least 50% of the farm is owned by the producer or the producer’s family members.

This is an important takeaway to remember, especially for those who sell to and serve farmers – family dynamics can, and often do, influence the farm business.

There are fewer smaller farms (and why that might not be the real problem)

One of the most popular panicky headlines that has been circulating from this Census is that “we’ve lost 7% of farms in only 5 years!!!”

However, there is one big reason that this is misleading.

The Census defines a farm as “any place from which $1,000 or more of agricultural products were produced and sold.” This dollar threshold was chosen in 1974. It’s important to note that the Census is not adjusted for inflation.

As we have all experienced in the past year, inflation can make a real difference. One thousand dollars in 1974 is actually over $6,000 in today’s dollars. Many of the farms that are considered farms today would not have met the bar to be defined as a farm when this most recent definition was created.

When we focus on the farms above that ~$10k threshold (in the brown box above), we see a different picture. Instead of a massive decline, the number of farms has remained relatively steady.

A note on US farms as one big happy market

When aspiring entrepreneurs hear that there are 2 million farms, they may lick their chops with anticipation. “What a nice, robust TAM (total addressable market)!” they may think.

There are two quick reality checks that burst that bubble:

The TAM shrinks by ~50% when you look at farms above $5k in revenue. There are 1,055,468 farms in 2022 that sold more than $5k in farm goods – compared to the 1.9M of total farms.

US farms are not one market. US farms are not one market that a company can simply treat all the same and hope to scrape the cream off the top; US farms are more like a bag of multi-colored confetti and finding the target market is carefully picking out the shiny pieces with tweezers.

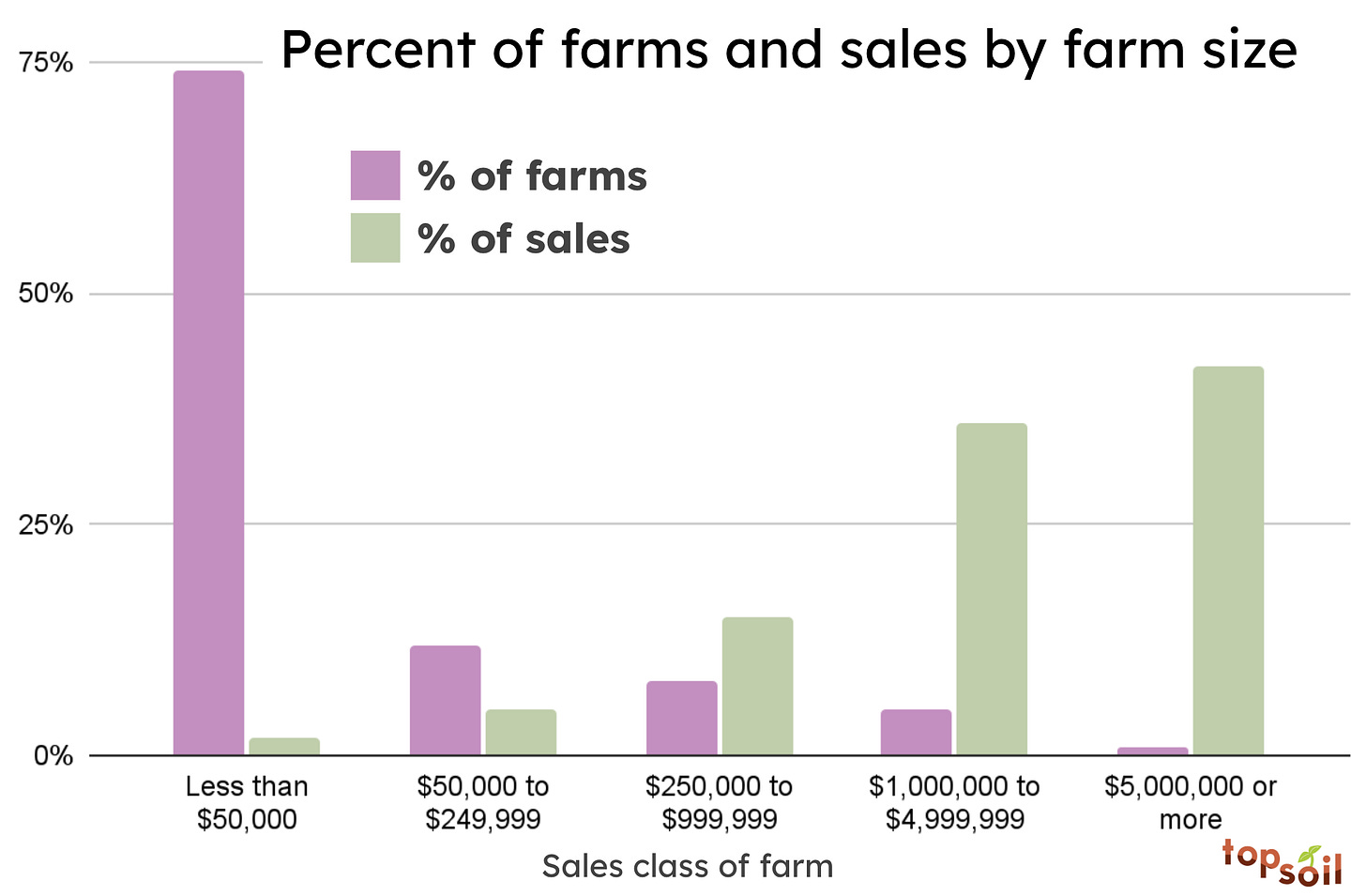

Finally, there is also an 80/20 rule when it comes to farm size and the amount that they produce: the largest 6% of farms by sales produce nearly 80% of all sales.

Fewer producers live on the farm

When we use “decline of small farms” as shorthand for “declining rural populations with a connection to the land,” the percent of producers who live on the farm may actually be a more meaningful statistic.

And when we look at the data, we find that there are fewer producers who live on the farms where they work. Twenty years ago, nearly 80% of producers lived on the farms where they worked. That number has decreased to about 70% today.

, a farmer in Iowa, wrote a beautiful piece on how this feels from the perspective of one person.Now, we don’t necessarily know why this trend is happening or all the downstream effects (are the farm houses still on the farm and just not occupied, or occupied by someone else? These are the things that the data can’t tell us). Some might even argue that the fertile farm ground that would be used for on-farm residences is more valuable as a field than a house.

I don’t have the answer to whether this is a good or bad thing. What I do know is that the Farm Census is an invitation to discuss, debate and define – what do we care about and why do we care about those things? Is there something inherently valuable or good about small farms or the ability for people to live on the ground they farm?

It leads us to consider what kinds of policies, businesses, and innovations should be developed to create the agriculture ecosystem that we would like to see thrive.

Government payments reinforce the status quo

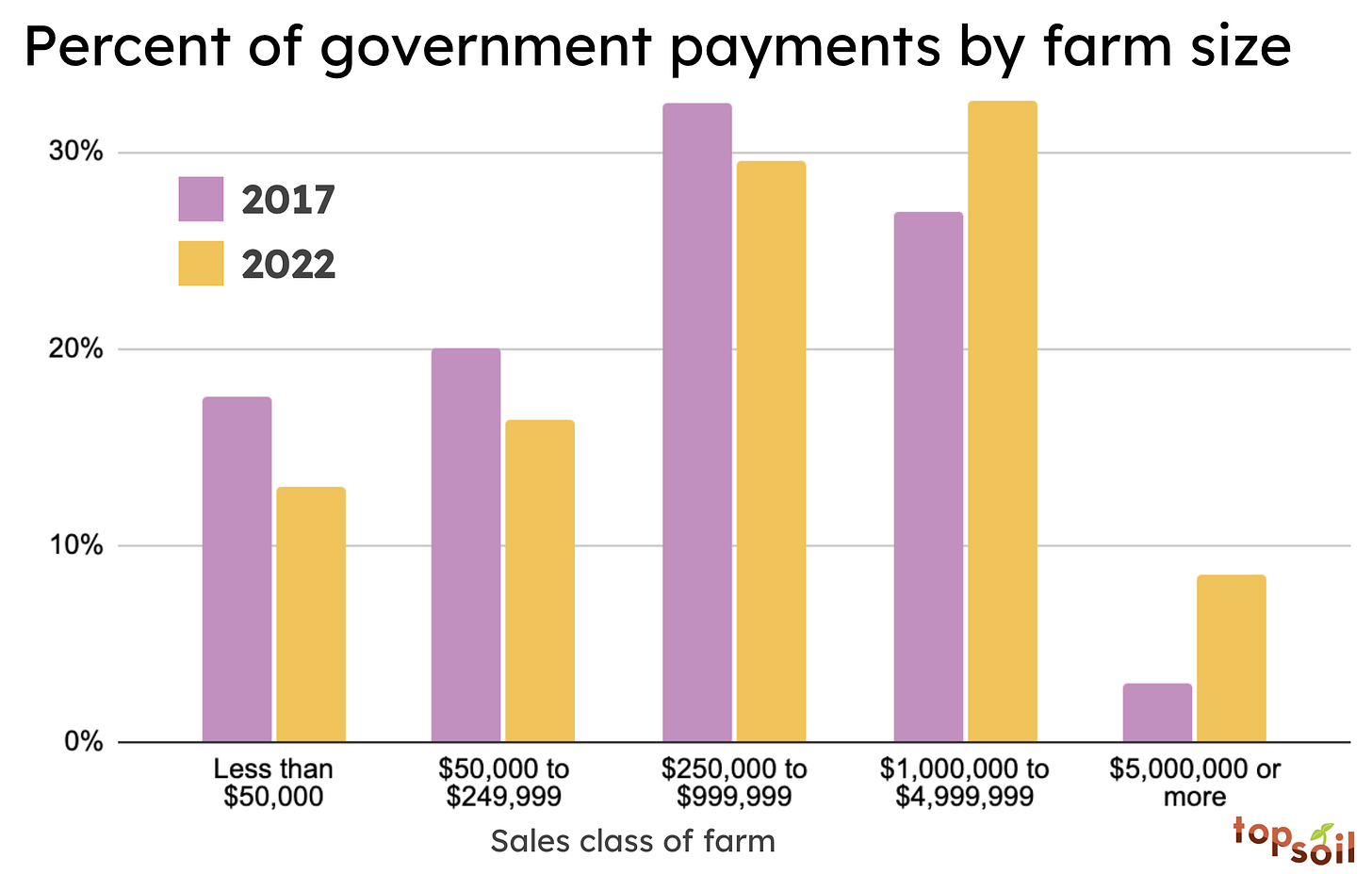

To that end, let’s take a look at government payments to farms by the size of the farm:

Overall in 2022, the Federal government paid out over $10 billion dollars to farmers through various subsidy programs, an increase of 17% from 2017.

This is one of the shortcomings of the Census data being from self-reported surveys. When compared to USDA’s records of actual payments, these figures vastly undercount the amounts paid out to farmers by the Federal government. In 2022, the actual amount paid out was closer to $15.5 billion dollars (and $11.5 billion in 2017 – in reality an increase of 35% over the five year period!).

One trend to take note of is that the largest farms are receiving a greater share of the Federal subsidy dollars. Recall that the farms with over $1 million in sales account for just 6% of the total number of farms in the US. These largest 6% of farms receive 40% of Federal subsidies.

By this measure, it is clear that Federal policy strongly favors the largest farms.

The top crops are still the top crops

While the overall harvested acreage is down between 2017 and 2022, the same crops that were in the Top 10 by acreage in 2017 continued to reign supreme in 2022:

There’s another 80/20 rule when it comes to crops and share of total acres covered: the top 10 crops account for 93% of all of the harvested cropland in the US.

While this tells us about how cropland in the US is used, it doesn’t necessarily tell us which crops are most profitable for farmers (and recall that specialty crops are often much higher revenue per acre than row crops).

There’s a lot more where that came from

While this whirlwind tour hopefully gives you a sense of US farms at a high-level and why we shouldn’t always believe the simple sound bites, we barely scratched the surface of all that the Census covers. There are entire sections on farmer demographics, farm financials, livestock, how land is used including adoption of practices like no-till and cover cropping, and new for 2022 – precision agriculture.

Speaking of precision agriculture, I had a great time chatting with Tim and Tyler Nuss recently on the

Podcast about precision agriculture which you can check out here!While the Census data is a helpful starting point, it’s important to remember that there is no such thing as an average farmer. Each farm is as unique as the people who run it, the choices that they make, the crops and livestock they grow, and the soil in their fields.

For folks who are interested in agriculture outside of the US, stay tuned! Next time, I’ll be back with more for you about another country that is an agricultural powerhouse. Thank you for reading!

Topsoil is handcrafted just for you by Ariel Patton. Complete sources can be found here. All views expressed and any errors in this newsletter are my own.

How did you feel about this monthly edition of Topsoil? Click below to let me know!

So if the 1980's farm crisis was the reason for the downtick in farmers age 45-54 then would not the next youngest age bracket be the recipient of the downturn? If so, then why do we not see a strong uptick in that age group? Maybe I'm missing something. I think what you will see moving forward is a slight uptick in younger farmers, but the largest majority of farm acres that transition will transition to existing farmers.

I am in the farm supply industry and farms in our state that do go out of business almost always sell to an existing farm. There are several reasons for that. It takes time to get a large enough line of credit and the farmer that is liquidating doesn't want the hassle of having multiple buyers and multiple legal transactions. Plus, existing farmers have long social relationships with their neighbors.