The Brazilian Way

A primer on a global agricultural powerhouse 🇧🇷

Welcome back to Topsoil! A monthly newsletter with frameworks to help you make sense of agriculture, at just the right depth.

This month, we are digging deep into one of the world’s agricultural powerhouses: Brazil.

To ground this edition, I had the opportunity to interview Fernando Palhares, a Precision Tech Strategy Manager at CNH Industrial and native Brazilian. Fernando trained as an engineer in Brazil and started his career in management consulting. He began to focus on agriculture after earning his MBA and MS in Agroecology at the University of Michigan. Over the years, he’s seen many different sides of agriculture through strategy and product roles at Granular, Cargill, Mahindra Agri and Mountain Hazelnuts.

Before we dig in, a no-brainer disclaimer: Brazilian agriculture is as big, beautiful, and diverse as Brazil itself – a country of 215 million people that spans four time zones. Brazil is actually larger in area than the Lower 48 of the United States. In short, this is a huge country. While we will be hitting the highlights, there’s much more that we won’t be able to cover.

Today, we’ll focus on Brazil’s rise, headwinds on the horizon, and a few things to consider when serving farmers in a different geography.

Let’s dig in!

Brazil: A 21st Century agricultural superpower

Beyond exporting festive all-you-can-eat steakhouses and some of the most beautiful people in the world, Brazil also is the third largest agricultural exporting country.

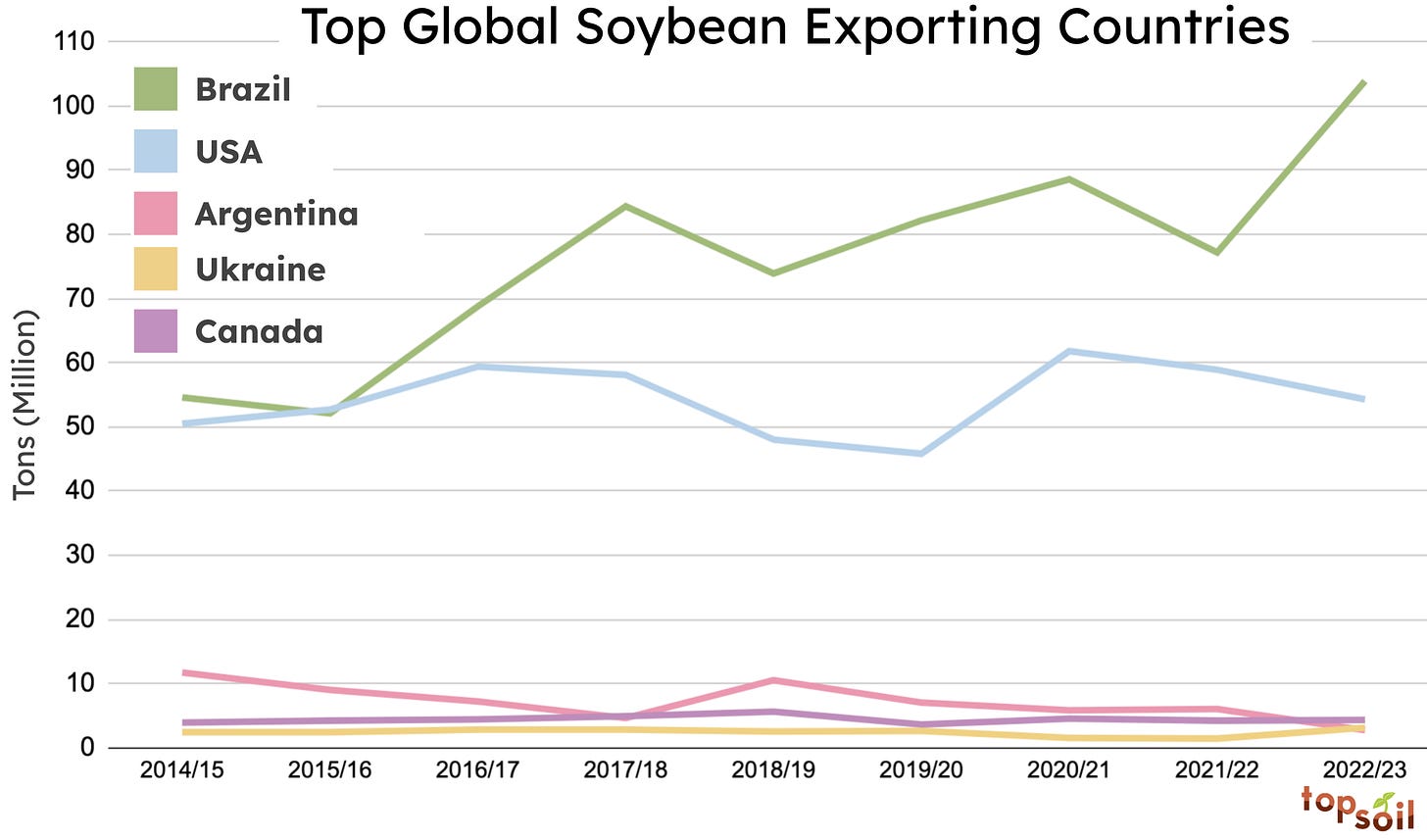

In 2013, Brazil became the world’s largest exporter of soybeans. A lot of this growth has been spurred by demand for livestock feed from around the world, particularly China.

In 2023, Brazil became the world’s largest exporter of corn. However, in 2024 the US is expected to take back that #1 spot based on current projections.

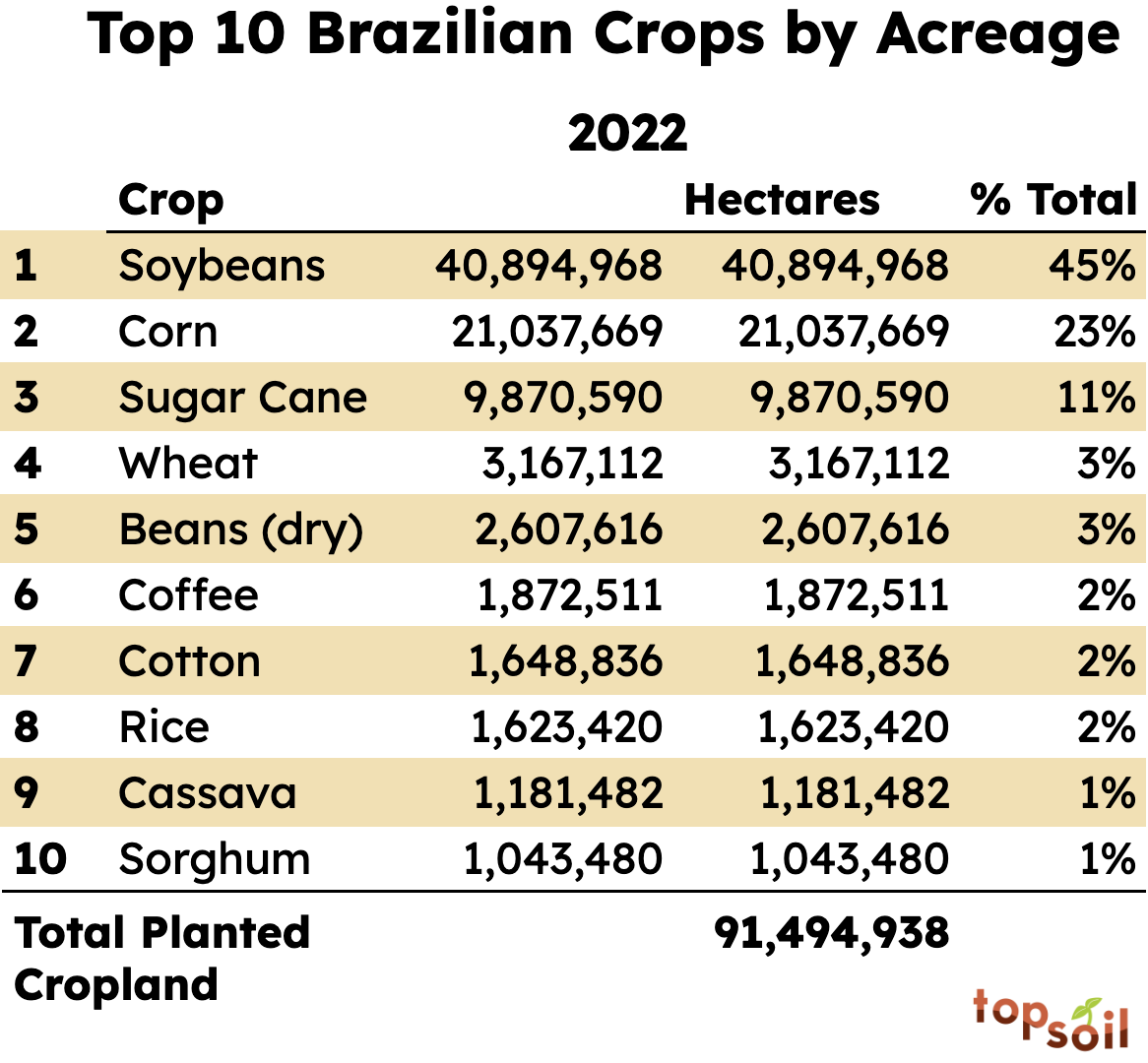

Beyond corn and soybeans, Brazil produces and exports many other crops – both commodity row crops and tropical crops like coffee and cacao.

Beyond its role as a key player on the global ag scene, agriculture is important within Brazil, accounting for nearly a third of the Brazilian GDP.

While Brazil’s agriculture exports have been on a strong up-and-to-the-right trajectory, it hasn’t always been this way. As Fernando explains, “if you look back 30 years ago, we were barely feeding ourselves and now we are exporting food to much of the world.”

Fernando attributes this glow up to two trends.

First, professionalization of many farms. “In the last 20-30 years, there’s been more access to capital. You have more market openings — foreign firms starting to invest here.” In addition to foreign investment, the Brazilian government has made an effort to extend credit to farmers and fund R&D through Embrapa, the state owned agriculture research organization. Through these efforts, farms have increased per acre productivity. Corn and soybean per hectare yield has more than doubled since 1975.

And second, is the expansion of farmed acres through farmland conversion. As a recent podcast observes, “Agricultural land does not exist until it’s made. We often look at land under cultivation today and go, ‘Wow! This is great farmland,’ forgetting the fact that at one point it wasn’t farmland. It only became farmland when people made it farmland.”

Fernando describes how this process goes in Brazil. “Usually, farmers on the frontier take forestland, chop down the trees and then introduce cattle. After securing land titles (not always legally), they start planting soybeans and corn on that plot.”

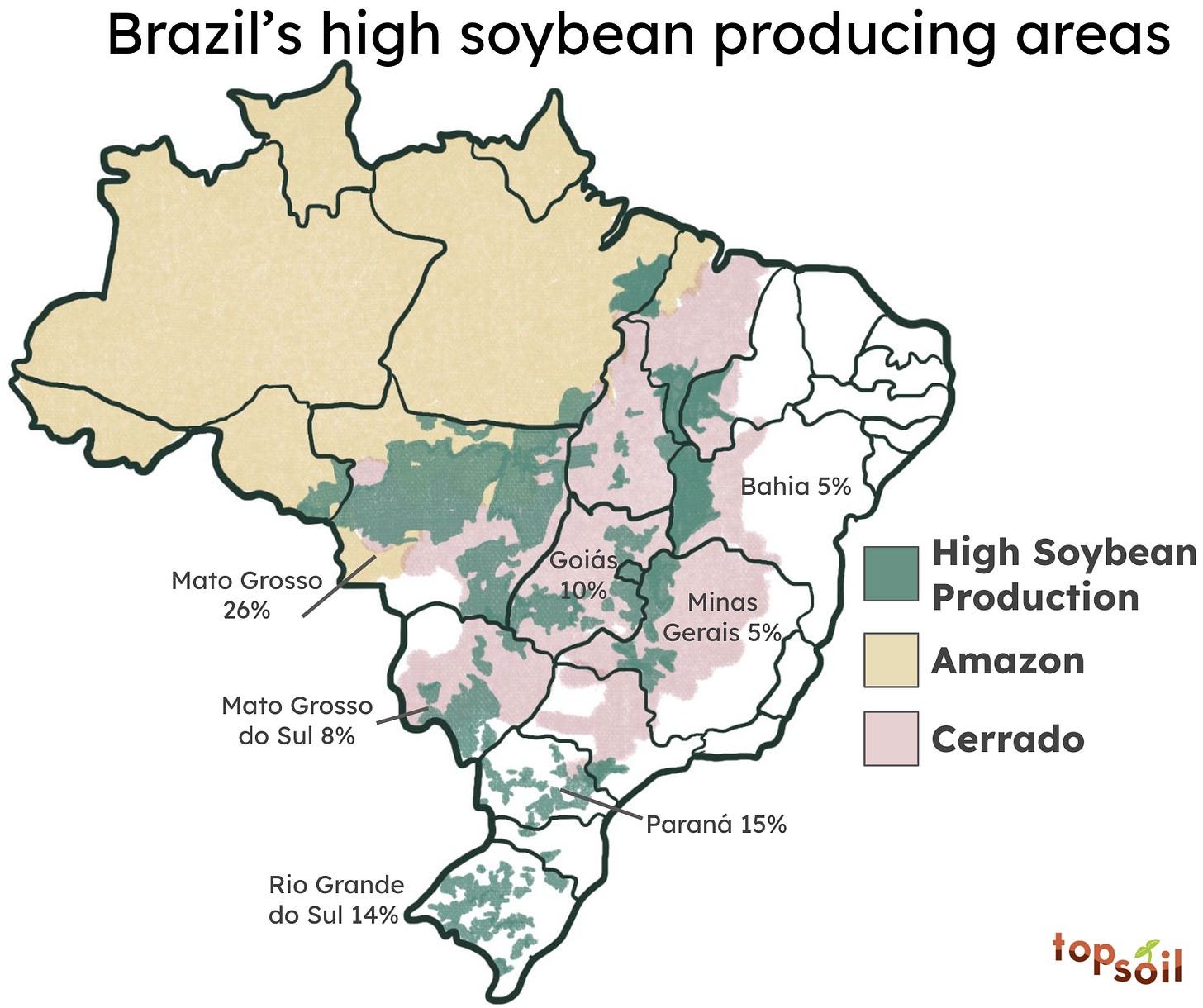

It’s estimated that about 1.5 million hectares (equivalent to 3.7 million acres) in Brazil are made into farmland each year.

Unfortunately, this has resulted in deforestation of the Amazon and the Cerrado. More than 19% of the Amazon in Brazil has been cleared since the 1970’s. The Cerrado, Brazil’s tropical savanna, has fared even worse with more than half cleared since the 1970’s. Beyond providing habitat for many unique species, these biomes provide many other ecosystem services like storing carbon dioxide and even moderating the weather.

There’s no easy solution. There are ample incentives for individuals to convert farmland, with few consequences for doing so. Strong global demand for cattle and grain around the world and weak traceability throughout the value chain make farmland conversion a rational, yet unfortunate, choice for many farmers.

As Fernando summarizes, “the tension between GDP, development and exports against conservation, biodiversity and environmentalism is the biggest moral dilemma Brazil faces in the near future.”

While the corn and soybeans produced in Brazil flow into the same global markets as commodities grown around the world, Brazilian agriculture has some unique qualities. Let’s take a closer look.

Welcome to the tropics

Brazil is close to the equator. Beyond warm, tropical weather, this means a few things:

There are multiple growing seasons per year in Brazil. Instead of harvesting one crop per calendar year like most of the other grain baskets of the world, farmers in Brazil can harvest two crops each year (and sometimes even three!).

Second, the tropics foster greater biodiversity. Brazil is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world, hosting over 15% of the world’s biodiversity and is home to over 4,000 plant species.

Fernando explains how this extreme biodiversity impacts agriculture with one example. “When I worked on LandVisor [a digital product for precise herbicide application] in Texas we had four types of weeds we were targeting on grasslands. But if you take a typical pastureland in Brazil, you have over 150 species of weeds. Because we’re in the tropics, ecological biodiversity is so much greater.” The same approaches that work in other parts of the world don’t necessarily work in Brazil.

The missing middle

Another striking characteristic of Brazilian agriculture is farm size.

As Fernando explains, “If you look at the way that most farms work in Brazil today, there are two separate poles. One is very big agribusinesses – way more concentrated than in North America. Then you have subsistence family farming.”

Similar to the United States, there is a bit of an 80/20 rule when it comes to the distribution of farm size and number of farms. In Brazil, a small number of large farms produce the majority of the farm profits while targeting mostly export markets; many small farms barely break even and serve mostly local markets. Seventy percent of farms are smaller than 50 hectares (~125 acres), while fewer than 0.5% of farms account for over half of the farm revenue.

Brazil is known for some of the largest farms by acreage. When we say large, we mean these are *truly* massive. We’re talking well over 100,000 hectares (~250,000 acres). Nova Piratininga is one example. This farm covers 135,000 hectares or 333,000 acres farming corn, soybeans, and cattle. To get a sense of scale, all five boroughs of New York City could easily fit within its borders!

These farms operate like billion dollar corporations, because many are. There are high levels of specialization among employees, with many operators and on-staff agronomists. Fernando mentioned how some large, vertically integrated farms even have their own software development teams to build custom solutions. Off-the-shelf software simply doesn’t cut it in many cases.

No surprise, technology adoption among these large farms is high – whether seeds with cutting-edge genetics, biologicals, equipment, or digital tools. Most companies who develop agriculture technology and inputs for Brazil target the largest farms.

In contrast, many of the small, typically family-run subsistence farms do not have access to new technologies and are often overlooked as a target market. These small farms tend to be less mechanized and require more manual labor. Instead of sending their crops abroad, the majority of the diverse crops produced are sold within Brazil. As we’ll see later, smaller farms also struggle to get financing.

Headwinds on the horizon

While growth has been strong, Fernando noted that farmers still face many challenges that don’t have easy solutions.

Exports in Brazil have exploded, but infrastructure is still catching up. Many key growing areas are not connected to ports via railway. Moving grain throughout Brazil is mostly done via truck, often on bumpy, unpaved roads.

Grain storage is costly. Many farms do not have on-farm storage, so must sell their grain as it is harvested. This weakens their ability to market their grain for better prices. Since so many farmers deliver grain at the same time during harvest, ports often have days-long lines to unload.

Beyond physical infrastructure, internet connectivity is sparse. As Fernando explains, “Most Brazilians have smartphones, but that doesn’t mean that telecom coverage on farms is like in the US. A lot of places won’t have even 3G, let alone 4G, 5G. Some bigger farms invest in their own WiFi networks to overcome that.” This explains why it was a big deal when John Deere recently announced the partnership with a satellite internet provider.

As we covered in a previous edition, farming requires careful management of cash since the seasonal nature of farming means that cash flows are lumpy. Credit – the ability to borrow money – is a critical tool.

Unfortunately in Brazil, Fernando shares that “less than half of farms have access to sufficient financing.” As you can probably guess, the biggest farms are first in line. Fernando adds, “This helps to explain farm size. If you’re a small farmer you can’t remain competitive because you just don’t have access to capital to buy your tractors and seeds.”

Demand for credit far outstrips the two typical sources: government credit and private credit. In addition, lenders struggle to assess the creditworthiness of small farmers, who are often left out. Fernando shared an example of a coffee farmer who owned a property worth $60M BRL. Even with that asset as collateral, this farmer was denied a credit line for $1.4M BRL. “The fact that big banks and credit co-ops are unable to structure credit for someone with so much collateral shows how behind the financial infrastructure is.”

Global trade is a double-edged sword. Brazil’s role as a major exporter has brought in new capital to spur development. On the flipside, farmers are impacted by things outside their borders.

On the import side, Brazil is “heavily reliant” on other parts of the world that produce raw materials like fertilizer. Because of the multiple crops per year, Brazilian farmers apply over twice as much fertilizer per acre per year as farmers in the US. Eighty-five percent of the fertilizer in Brazil is imported.

On the export side, Brazil is heavily dependent on China. Over the last five years, 73% of the exported soybeans were sent to China. As China begins to increase its own domestic production, this could spell trouble for Brazilian farmers.

Like farmers in every other part of the world, Brazilian farmers are at the mercy of weather. And, like many other parts of the world, the weather in Brazil has become more extreme with climate change. Deforestation locally also exacerbates swings in weather. To make matters more difficult, crop insurance is much less common in Brazil than in North America.

As of this writing in April 2024, parts of Brazil are facing both droughts and floods, strongly influenced by the El Niño weather system. Oftentimes, extreme weather hits the small farmers hardest since their farms are more concentrated geographically.

In short, Brazilian farmers have their hands full.

Despite these challenges, Fernando described the concept of “jeitinho” – the ability of Brazilians, including Brazilian farmers, to overcome obstacles through creativity, resourcefulness, and cleverness.

“We Brazilians always find a way.”

Serving farmers the Brazilian Way

To support Brazilian farmers, many homegrown companies have emerged to tackle some of the challenges above. Since agriculture can often be a don’t-know-it-’til-you’ve-seen-it kind of business, local experience can be a game changer.

Some companies are addressing the lacking infrastructure by improving grain logistics (Strada) or making it easier for commodity buyers and sellers to connect digitally (Grao Direto). Others, like Campo Capital, help small farmers access credit through peer-to-peer lending.

For those beyond the borders, Brazil is often a “must-win” market. A steady stream of companies have entered Brazil by either buying Brazilian companies (like Syngenta acquiring the popular farm management software, Strider), partnering with Brazilian companies (Grao Direto has financial backing from nearly all of the global majors: Cargill, ADM, Louis Dreyfus, Bayer and BASF), or building their own solutions with a Brazilian flavor.

Fernando had some great advice for those who enter the Brazilian market, or are internationalizing their products for a new audience (casually called “i18n” in the biz):

Meet the customers where they are at. Product development and distribution will need to meet Brazilian customers’ unique needs. For example, new technologies like See & Spray that use computer vision to identify weeds will require massive amounts of local data to identify the much broader array of weeds.

As far as ways to reach the customer, independent retailers are critical (41% of inputs are sold through this channel). However, Fernando shares, “Brazil is where the US was 15 years ago on the retail side as we still have a very fragmented landscape. Rolling up and consolidation is playing out right now in Brazil.” Any sales approach will need to work with many distributors.

Avoid dumb mistakes. Fernando shared a story after speaking with a handful of Brazilian farmers. After importing tractors to use on their farms, they were upset: “Why do companies keep sending us tractors with snow covers?!” Spoiler alert: snow is not a problem that Brazilian farmers face.

There are other easy mistakes to avoid. Fernando shared, “don’t assume that people, especially operators, speak English.” Instead, any instructions or interfaces should be in Brazilian Portuguese. The units of measurement are hectares and the metric system is preferred. WhatsApp is the dominant communication channel. Simple product choices can go a long way to show respect for the customer.

Don’t be a tourist. There are many examples of companies making major fanfare as they launch a product to a new market, only to peter out a year or two later and retreat. While it’s important for businesses to cut losses when something isn’t working, it can leave farmers in the lurch who have invested their precious time and money to try something new. The decision to enter any new market should not be made lightly.

Topsoil is handcrafted just for you by Ariel Patton. A big shoutout to Fernando Palhares for sharing his experiences with me, wrangling data and editing. Complete sources can be found here. All views expressed and any errors in this newsletter are my own.

How did you feel about this monthly edition of Topsoil? Click below to let me know!

Ariel

I have often heard that the is little storage in Brazil. Why is that? Is the climate such that it would be difficult keeping the grain from spoiling?

Reading this newsletter is great, but helping to co-write it is even better! Thank you for the opportunity and for the trust, Ariel :)