Hello from rainy California where the rivers and banks are running (too soon?) and welcome to the many new faces here! 👋 I am thrilled to bring you this month’s edition of Topsoil, frameworks to help you make sense of agriculture, at just the right depth.

Last week, I had so much fun being a guest on the Modern Acre podcast where hosts Tim and Tyler Nuss and I talk about seasons in depth (yup, they’re still a thing). I’ll be on the Modern Acre podcast again later this month to deep dive into the business of farming which should be a blast, especially since Tim is working on his farm’s budgets as we speak.

Let’s dig in!

Farms can be many things – a family legacy, a lifestyle, or the backdrop to many children's books. Today, we are going to make sense of the dollars and cents of farming. We are going to talk about farms as a business.

To help us understand farms as businesses, we’re going to lean on a concept that has been around for over 7,000 years and used across most industries – accounting. For those allergic to accounting, fear not! Instead of going through each statement in detail, we will dig into the pieces that make farm businesses unique.

The levers that drive profit and loss

Farms, like most businesses, aim to be profitable. But what exactly is profit?

Profit is what is left over after your costs (money out) are subtracted from your revenue (money in). If your costs are greater than your revenue, that is considered a loss.

Farms make revenue through a couple common ways:

Selling crop products like grain, vegetables, fruit and nuts: Revenue from crop products is a function of yield multiplied by price. In most cases, farmers sell their crop products into competitive commodity markets and are often price takers, meaning they have no control in setting the price of their crop products sold.

Subsidies from the government: Because the production of food, fuel and fiber is deemed critical to a nation’s health and security, many governments around the world subsidize farming. For example, in the US over the past 5 years, farmers have received nearly $120 billion (with a “b”). While not evenly distributed among the roughly 2 million farmers nationwide, that pencils out to about $60,000 per farm in direct government payments.

Farms have to spend money to make money. Typical costs for a US farm include:

Land: Land can be rented or owned and can be highly variable in terms of soil quality and productivity.

Inputs: Inputs are all the things applied to produce a crop and include:

Seeds or plants

Fertilizer: Nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K) are the main nutrients a crop needs, and there are many others, like lime and micronutrients that are critical to plant health and yield.

Crop protection: Weeds, pests and diseases can harm crop productivity, so this category includes all the “-cides”: herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, nematicides, and more.

Water: In places where there is insufficient rain, crops must be irrigated which requires infrastructure, equipment, and paying the cost of the water.

Labor: There are a variety of jobs across the farm in order to produce a crop. Even the most automated farms still require some level of human labor.

Equipment: Farms vary in their level of automation, but in many cases, specialized equipment is used for certain jobs on the farm, from planting, to spraying, to harvesting and hauling.

Putting it all together, a farm growing a commodity row crop like corn in the US Midwest might look something like this:

While this table shows a tidy profit of $102.41/acre, in reality, this bottom-line performance can vary depending on a complex, interrelated set of factors including region and rotation (there are numerous other estimates out there to demonstrate this variability).

Some of these factors are outside of a farmer’s control, like market prices, weather, and interest rates. Farmers have more control over certain other (related) factors, like deciding which crops to grow or which management practices to apply to their ground. There are estimates that farmers make over 140 major decisions in a year – each one a lever to impact their revenue or costs and drive towards profitability.

We’ve looked at commodity grain farms so far, but we know that one size does not fit all when it comes to crops. A specialty crop like strawberries looks very different, something like this:

Unlike its commodity corn cousin, the revenue for an acre of strawberries is astonishingly high, at $90,000 per acre. However, the costs across the board are also radically higher. By these estimates, the labor cost for strawberries is 1,000 times higher than the labor cost for corn, and the land cost for strawberries is 100 times higher than that for corn. As a result, by this estimation in 2021 for strawberries, there is a per acre loss of $2,341 if all of these assumptions hold true.

Now, this is emphatically not a statement that corn is a better business than strawberries.

I share these two examples to demonstrate the complexity of growing a profitable crop. While there are many levers that a farmer can pull, in many cases, farming is simply a low-margin business – there is not much room between the revenue and the costs. In the corn example, if the price of corn drops just 10%, suddenly, that acre is no longer breaking even.

This fact puts tremendous pressure on farmers to farm more acres. If you’re only making $100 per acre in a good year, to make farming as a business worthwhile, it takes many acres to support a livelihood and reinvest for future years.

Consider your own paycheck today. How many acres would you need to farm in order to make your income? To make matters even tougher as we see with the strawberry example above, in some years on some acres, farmers actually lose money!

Cash is king

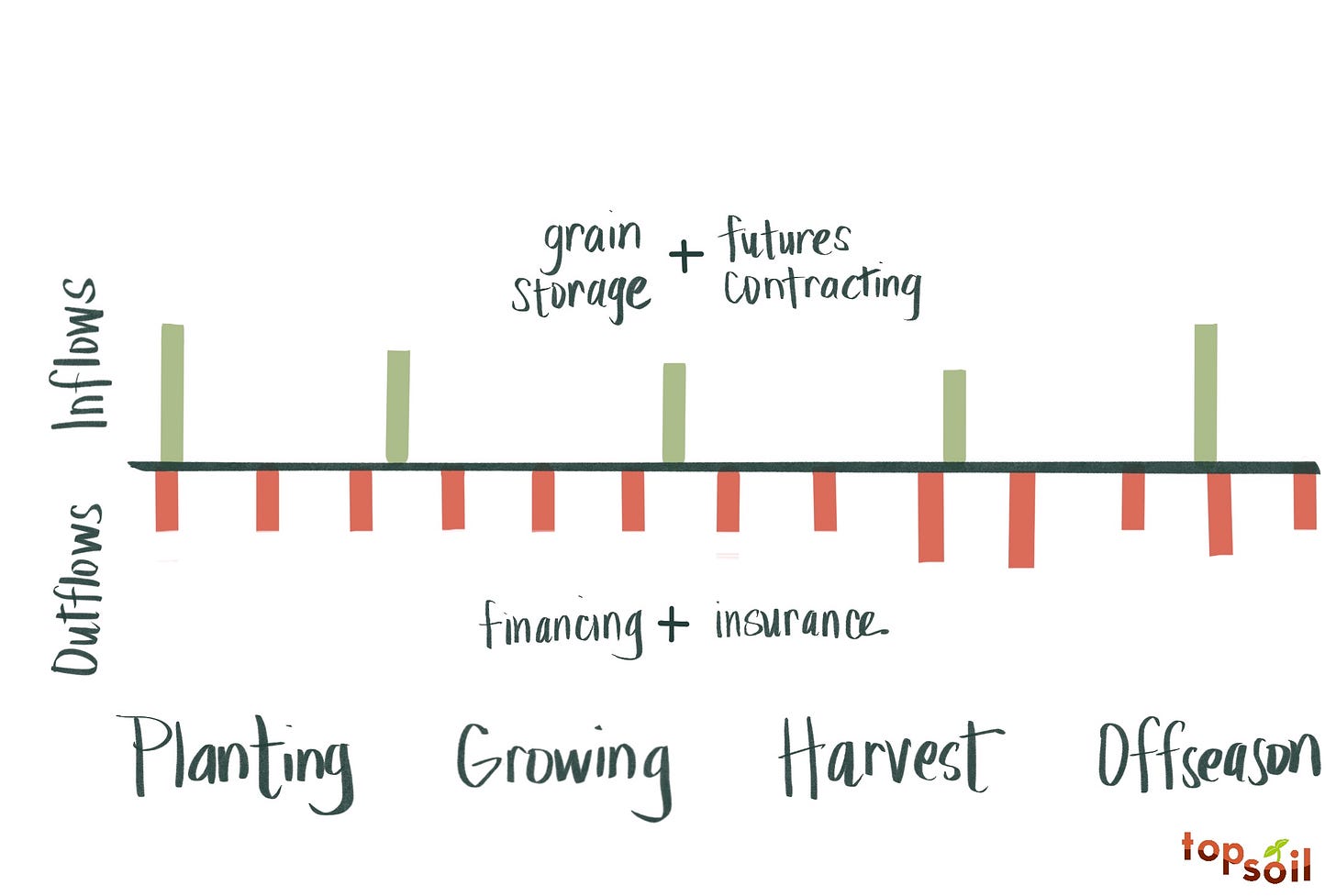

Because of the seasonal nature of agriculture, the cash flows to a farm are “lumpy”. Cash flows out during the season – in the spring, farmers bury their cash in the ground in the form of seeds, they spray cash on their crops to protect crop yield in the form of inputs, they tie up cash in equipment to ensure they can harvest in a timely fashion once the crop is mature. As the crop is harvested and farmers finally have grain or produce they can sell, cash flows back into the business.

“Cash is more important than your mother” was a favorite saying of one of my finance professors in business school.

While that sounds like a totally insane Scrooge McDuck thing to say, my professor would quickly follow up with “your company can survive without your mother, but your company cannot survive without cash.”

That statement is true for many companies, and farms are no different. Not having cash on hand when it is needed to cover expenses can lead to selling off assets, weakened credit, and ultimately bankruptcy.

Though unlike many industries, in agriculture in the US, 98% of farms are family owned and operated – if you are a farmer, your mother might also be the farm bookkeeper, run the planter, and shape strategic decisions across the farm. Your farm may very well not survive without cash or your mother!

Lumpy cash flows present a risk. If you remember nothing else, farming is one big exercise in risk management. To manage the risk of lumpy cash flows, farmers use a variety of tools from financing with operating loans, to insurance, to grain marketing strategies like storage and futures contracts to smooth the inflows and outflows of cash. When these tools are used, the inflows and outflows become more predictable for the farmer to manage:

Many companies that sell to farmers provide credit and other financial services to sweeten the deal when farmers buy their products. For example, in order for John Deere to sell $47 billion of equipment in 2022, they provide financing to their farmer customers. How much financing? In 2022, John Deere had $36 billion of loans and operating leases outstanding to customers.

Beyond the lumpiness of the cash flows of a single season, many perennial crops have another dimension of lumpiness across several years. For example, walnuts need a large up front investment to establish an orchard but do not start producing a crop that can bring in revenue until the 4th or 5th year after being planted.

Farming is an asset-heavy business

Given all of the above, it might be surprising to learn that farmers in the US are much wealthier than the median American.

However, this wealth is tied up in the ownership of assets like land and equipment – as much as 80% of wealth in the agricultural sector is tied up in farmland alone. To many farmers' dismay, this does not always translate to seeing cash in their bank accounts which is why the phrase “rich on paper and cash poor” may ring true for many farmers.

In Sarah Mock’s fascinating podcast on farm debt, a guest notes “agriculture is the only industry where we think it’s a positive when the cost of the factory goes up,” referring to the rising cost of farmland. Farmland is not only the productive “factory” where crops are grown, it is also used as collateral for loans and operating lines of credit so that farmers can access capital to make purchases (and manage those lumpy cash flows as we showed above).

When the price of farmland goes up, as it has continuously over the past several years, it means that farmers who own farmland can access more credit. However, if farmland prices were to go down, say as a result of rising interest rates, this could put farmers in a tough spot if they borrowed heavily against their farmland assets.

Farmers wear many hats – they must act as biologists, mechanics, traders, and more. I have a deep respect for farmers as business people because with tight margins, the need for thoughtful cash flow management, and the double-edged sword of rising farmland prices, it’s impossible to ignore the underlying business fundamentals and stay farming for long.

Topsoil is handcrafted just for you by Ariel Patton. All views expressed in this newsletter are my own. Complete sources can be found here.

How did you feel about this monthly edition of Topsoil? Click below to let me know!

I didn't know until know that marings are so small! It means that ag-tech companies have to give very compelling offerings, if we want our customers to take a risk.

Love the piece, Ariel. Thanks for sharing! My reflection:

Size really matters. In a “large” production system, a farms success becomes increasingly dependent the farmer adopting an “asset management” perspective over the traditional “operational” perspective. Often requiring leverage into other assets or businesses.

A small DTC operation can be wildly more profitable than a production model based on an opposite mentality - prioritizing ops.