Farming is a team sport

A framework for roles on the farm

Before we jump into our topic today, I want to welcome new subscribers 👋 and share a recent podcast appearance. I joined Tim and Tyler Nuss on the Modern Acre Podcast earlier this month to chat about weeds and weed control of the future. Feel free to check out that episode by clicking here!

Thank you for your continued support in reading, subscribing and sharing Topsoil – a monthly newsletter with frameworks to help you make sense of agriculture, at just the right depth.

It’s no secret that farmers wear many hats.

Running a farm takes many different skills – working in the field, managing financials, fixing equipment, buying inputs, and selling the crop, planning for next year, among many other jobs.

For some farms, one person can do all of those tasks. For many other farms, it takes a team.

Today we’ll cover some of the roles on the farm, off the farm, and what these roles mean for businesses that work with farms. Let’s dig in!

Roles on the Farm

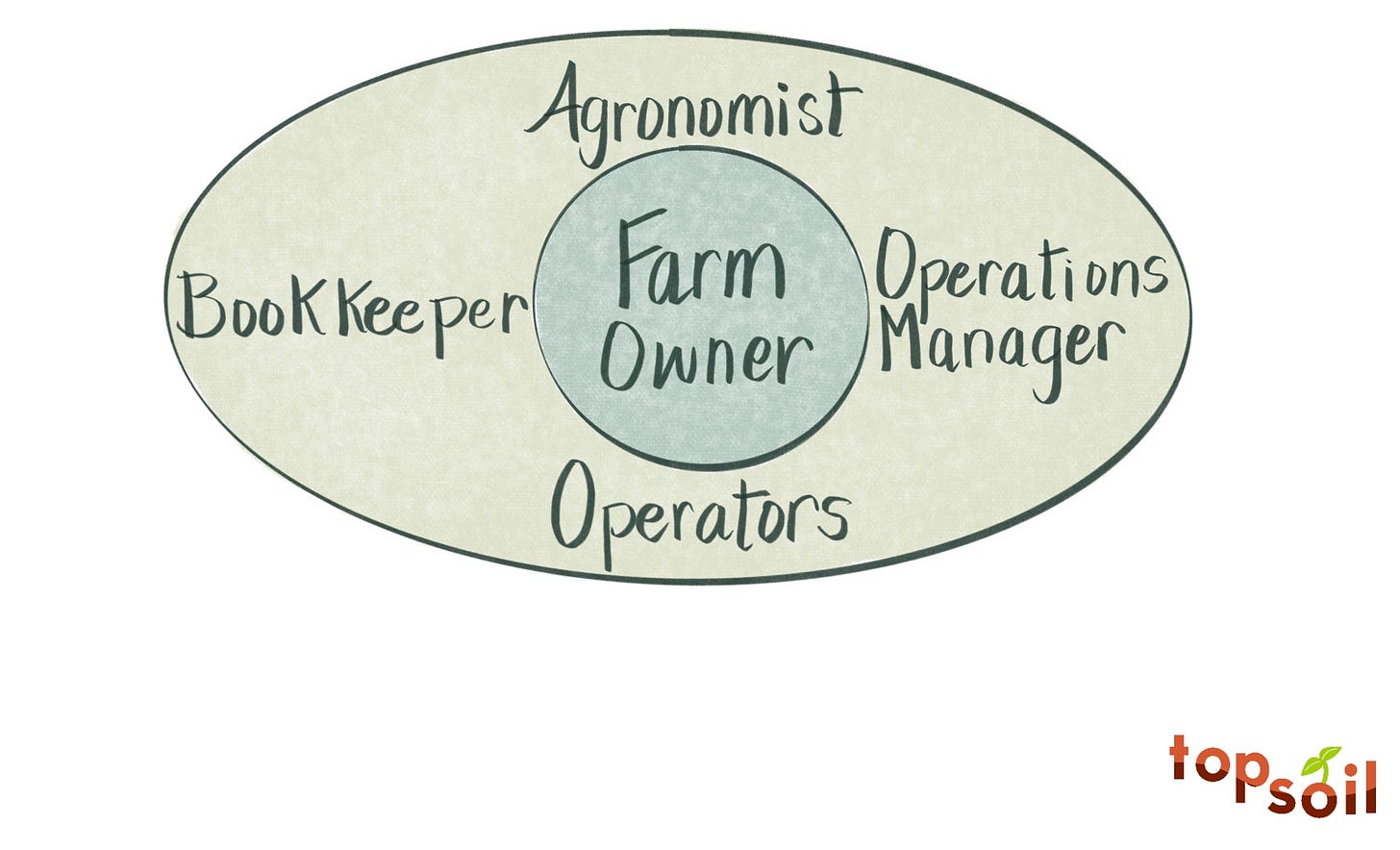

First, we start with the farm owner. This person is often called the “farmer” (or “grower” or “producer” – a heated terminology debate for another day!) who owns the farm business.

Beyond the farm owner, there are several other roles on the farm. The farm owner may perform some, if not all, of these other roles. For example, it is common for the farm owner to be the operations manager.

In many other cases, especially as farms grow in acreage or revenue, not surprisingly, employees are hired or contracted to fill these other roles.

Operations Manager: This person makes sure stuff gets done across the farm. If that sounds broad, that is because it is. They are typically responsible for planning ahead that people and resources are in place to get field work done and troubleshooting when things break down in the field. This person manages the operators, directing who needs to go where and when to get work done.

Operators: These are the people who are responsible for executing the fieldwork, depending on what the season calls for: planting, harvesting, tillage, spraying, picking, mowing, pruning – you name it. Many operators (or “farmhands”) are employed by the farm. In other cases, where labor needs fluctuate heavily throughout the season, operators will work on a contract basis or get brought on through middlemen farm labor contractors. Some operators have specialized expertise, for example, in equipment maintenance and repair.

Bookkeeper: While much of the work on the farm happens in the field, office work goes on behind the scenes to keep the farm running. The bookkeeper keeps records straight and keeps tabs on the money going in and out of the farm. This means paying bills, invoicing for any custom work, reconciling bank accounts, entering data, and making sure employees get their paycheck.

Agronomist: This person (sometimes called a “crop advisor”) is an expert in agronomic practices – particularly soil and plant health. The agronomist guides cropping decisions, makes fertility and seeding prescriptions, scouts the field for threats to crop health to recommend treatments, and takes soil samples. In many cases, the agronomist will manage agronomic data to inform recommendations for the next season.

In the US, 98% of farms are family owned and operated, so it’s not uncommon for family members to be involved. The family business dynamic makes agriculture unique and can create challenging situations, like succession planning or tactfully managing family-members-as-employees. Ideally, this entails less drama and mayhem than the Dutton or Roy families!

Every farm operates a little differently depending on where in the world it is located, the crops produced, and local labor availability. Not every farm will employ these roles, or may use slightly different titles. In many cases, it makes sense to outsource this work. That brings us to a broader supporting cast of characters.

Beyond the Farm Gate

While these additional roles may not be directly employed by the farm, they work closely with the farmer on a regular basis. Many of these are referred to as “Trusted Advisors.”

Trusted Advisors (rarely just “Advisor”) is a common phrase in agriculture that always tickles me. It makes me wonder, is there anyone you take advice from whom you don’t trust? I’ve been workshopping similar phrases, but none have really stuck so far. Like, “I’m going to get tax advice from my Honest Accountant” or “I just had a root canal from my Competent Dentist”. They just don’t quite have the same ring as “Trusted Advisor.”

In any case, trusted advisors often provide a mix of products and services to the farm. Initially, many of these roles, like ag retailers or equipment dealers, were simply product salespeople. As products have become more commodified, many salespeople have begun to offer service and advice to differentiate themselves.

Ag retailer: As we covered in the Ag Value Chain, farmers often buy the inputs they need, like fertilizer, seed, and crop protection, from an ag retailer. Oftentimes, the ag retailer staffs salespeople, applicators, and even sales agronomists who provide service and advice to farmers.

Seed dealer: Certain seed brands (like Pioneer) do not sell their products through ag retail, and instead sell their products directly to the farmer through a dedicated sales team. Similar to ag retailers, these seed dealers often strive to provide outstanding service to stand out from the competition.

Equipment dealer: Whether equipment is green, red, or something in between, the equipment dealer is a critical partner. They sell equipment, provide repair and maintenance services, and increasingly, offer advice on data collection and management.

Insurance agent: Given the unpredictability of weather and geopolitical events that influence crop prices, crop insurance is a staple for many farms (especially since it is subsidized by governments like the US for certain commodities). An insurance agent (or “crop insurer”) sells insurance policies and coverage to farmers.

Buyer: Crops must be sold in order for farms to be profitable. This may look different depending on the crop grown. Typically for commodity row crops like corn or soybeans, farmers work with a grain buyer (or “originator”) to sell their grain, oftentimes under futures contracts. Specialty crops like fruits, nuts, and produce, also are sold under contracts or in “spot markets” for immediate delivery. Some farms will work with an independent marketing consultant to sell their crops.

Accountant: While many farms conduct basic bookkeeping activities on the farm, when it comes to filing taxes (and suggesting ways to minimize taxes), or longer term financial planning, many farms work with an external accountant.

Ag Lender: Since cash flows in farming can be inconsistent, it’s critical that farmers work with an ag lender (sometimes referred to as a “loan officer” or simply “banker”) to ensure they have operating credit for expenses throughout the year as well as the ability to get loans as needed for bigger purchases like land and equipment.

Landlord: Over half of cropland in the US is rented. As a result, many farmers interact regularly with their landlord or landlords. As of 2014, two-thirds of landlords are individuals or partnerships, with the remaining one-third being corporations, trusts and other investors who own farmland.

The Farm Crew of the Future and How to Serve Them

If you are in the business of reaching farms with new products or services, there are a couple of takeaways:

There are several roads to the farm. In the “AgTech 1.0” era (think farm management software of the early 2010’s), agtech companies smiled and dialed across the countryside to sell directly to farm owners. This resulted in limited growth and adoption. In the “AgTech 2.0” era and beyond, companies like Bushel and AgVend have had greater success by serving grain elevators and ag retailers first, and then developing solutions to connect to the farm. Furthermore, Seana Day did an excellent analysis of agtech investment over the past decade and found that even in 2023, there has been little innovation in tools for ag service providers, who ultimately serve the farm (which smells like an opportunity to me!).

The person writing the check and the person using the product might not be the same person. Imagine you are creating a new software tool for farm bookkeepers to keep better track of farm expenses. If you want product feedback, it will be important to actually talk to the person using the tool – the bookkeeper in this case. Your marketing and sales team will also need to talk to the farm owner, who may be the one writing the check. Two different roles with different needs that must both be considered for your product to be successful.

Finally, your gal loves nothing more than to speculate on the future of agriculture. So what will the farm crew of the 2030’s look like?

There are some things that we can count on to remain the same – like the importance of relationships in agriculture. “Ag is a relationship business” is a common belief that has staying power. The roles above address real needs that are not going away anytime soon.

While relationships will remain important in agriculture, there are a few growing trends that will shape the day-to-day activities of those roles and how they interact.

There is increasing consolidation of farms, meaning that farms are getting larger. In many cases, this means that the same crew is working across more acres. It also means that the roles beyond the farm gate will have fewer, larger farm customers. This will likely trigger consolidation among those service providers beyond the farm gate as well.

As a result of farms becoming larger and having more access to information, farms are professionalizing. Kristjan Hebert, a Canadian grain farmer, is a great example of a farmer who runs his operation as an innovative business and strives to bring top talent to his team as his farm grows.

This combination of fewer, larger, more professional farm customers puts pressure on ag retailers, equipment dealers, and other off-farm roles to step up their game. Shane Thomas and Sarah Nolet discuss in a fantastic conversation how ag retailers in particular must adapt to these changes.

Finally, advances in technology are driving automation on the farm. The word “automation” might spark fears that robots are coming for your job. However, the number of farmworkers has remained relatively steady since 1990. In many cases, there is a labor shortage in agriculture. As Rhishi Pethe shares, robots and other technology can be “a way to augment human capabilities rather than to replace them completely.”

As we think about the farm team of the future, and especially new technology like artificial intelligence, it is likely that the mix of tasks will change, but the need for people won’t change. Automation can fulfill repetitive or lower-skilled tasks, which will help humans use their time for higher-skilled tasks.

As a result, the human farm team will require training to not only harness new technology, but also spend their newly freed time on other higher-value pursuits across the farm. A simple example today: as yield mapping software has improved over the past several decades, agronomists don’t have to spend huge amounts of time getting the yield maps to work and can instead spend their time turning those yield maps into valuable recommendations and services for their farmer customers.

Now for the real heated question – who on the farm is the team MVP? Curious to hear your thoughts in the comments below!

Topsoil is handcrafted just for you by Ariel Patton. Complete sources can be found here. All views expressed and any errors in this newsletter are my own.

How did you feel about this monthly edition of Topsoil? Click below to let me know!

Thank you so much for this article!

As always, it's an interesting and profound analysis!

Let's start from the end – the most valuable player will be the one who creates a comprehensive IT farm management system based on clear data and AI algorithms, integrating all external and internal data sources. 🚀

This will serve as the primary framework for business planning and operational management, providing data for accounting operations and tax reporting. 📊💰

In this ideal scenario, a 👨🌾farmer will be able to open the 📱application in the 🌄 morning and ask the system (as Rhishi discussed in the latest issue about using LLM technologies),

"Hello! What's on our agenda for today? Please show me the current operational plan and yesterday's performance. How much money is in the account? What's the grain volume at the elevator? What payments are due today?" 💼

In Ukraine, we've already been fantasizing about this, collecting historical field data from various sources. 😉

The model of agri-operations can be well-described for all segments of agribusiness, making it easy to see where the need for human labor is reduced and indispensable. 🤖

🚜 Autonomous machinery will undoubtedly reduce the number of operators but will still require human involvement in the process of delivering goods to the field and loading them into the equipment.

Of course, at some point in the future, we'll reach a fully automated process from delivery to loading without human intervention, at the level of system identification and docking, much like spacecraft.🚀

👨🌾Staffing issues are specific to each country and segment of agribusiness. Given my previous experience with large agribusinesses, they have separate KPIs for the number of staff per 1,000 hectares (2,400 acres). 📉 The process of personnel optimization through process automation and organizational restructuring is ongoing every year. From memory, ten years ago, the average number of employees per 1,000 hectares was around 20-25 people, whereas today, a good benchmark is considered 10-12, and an excellent one is 7-8!

🎯I wonder if American farmers have similar metrics? 🇺🇸

The examples of Bushel and AgVend are spot on.

They each approach the farmer from their end of the process, creating a chain from input suppliers to farm management and the sale of the final product. AgVend wants to understand the market 📊 balance for planned farmer purchases of inputs for agri-retailers to balance the supply chain. A great idea! 🚀

Thanks for the link to the article "What is 'the next big thing' for agtech?"

After reading your text, I'm even more excited about the new possibilities I'm discovering as I delve deeper into the specifics of working in the U.S. agribusiness. 💰🌾🤝

It sure seems like automation should be a welcome development to agriculture, with labor shortages already here. Technology is not to be feared, it's a natural progression!