Welcome back! I am thrilled to bring you this month’s edition of Topsoil, a monthly newsletter with frameworks to help you make sense of agriculture, at just the right depth.

Farming is most often a family affair. In the US, 96% of farms are family-owned and operated. Anyone who has played a game of Monopoly with their siblings that ended in tears can understand that when family and business mix, there are complexities that go far beyond a regular desk job.

This month, we’re discussing one unique aspect of family farm businesses: succession planning.

Succession planning allows farmers to answer “what happens next” to their farm when they step down at the end of their career. In many cases, it means passing the farm from one generation to the next.

To guide this discussion, I had the opportunity to interview Lauren Riensche, who understands this topic from many angles. She grew up on her family’s six-generation corn, soy, and wheat farm in Iowa. She and her husband continue to farm in Iowa today. Lauren has also worked with thousands of farmers as she has led commercialization and marketing efforts for leading brands across the agricultural industry, including Farm Journal, Kent Nutrition Group, Case IH, Granular, Monsanto, Bayer Crop Science, and most recently, Indigo Ag.

Today, we’ll cover what succession planning is, how it looks across many farms, and why it matters far beyond the farm gate.

Let’s dig in!

Not your typical 9-to-5

Farming is much more than just a job. In a survey taken of US farmers, 78% said “non-financial goals” were more important than financial goals in running the farm. It follows then, that retirement from farming hits differently.

Lauren shares, “When you have your identity intrinsically tied up in the farm, it's more than retiring from a job. You cannot think of retiring as you would a 9-to-5, there's no party. It's actually more often than not a morose event than a joyful one.” (Side note: any quotes are from Lauren unless otherwise noted)

There are many reasons why a farmer might ultimately step down. Oftentimes, poor health will force a retirement. Within every farm community, there are stories of a heart attack or stroke tragically ending a career and surviving family members scrambling to pick up the pieces.

In less drastic cases, a farmer may no longer feel the drive to keep up with the advancements and relentless demands of farming. Lauren shares, “If it's not in your bones anymore, it may be time to retire, if able.”

In other cases, a farmer may notice that others, like their long-time seed dealer or mechanic, are winding down their careers. “If your peers of 30 years are turning in their company trucks for condos at the beach, that might take away some of the familiarity and joy for you.”

There are more logistical reasons a farmer may call it quits. Some farms “run out of monetary resources to continue to farm” when the financials no longer pencil out. For others, the “complexity comes to a point where the tech, the systems, the programs, the laws, the equipment may become so complicated that it is not within a farmer’s bandwidth to stay up to date.”

Whether it happens slowly or all at once, at some point – a farmer retires. So what happens to the farm then?

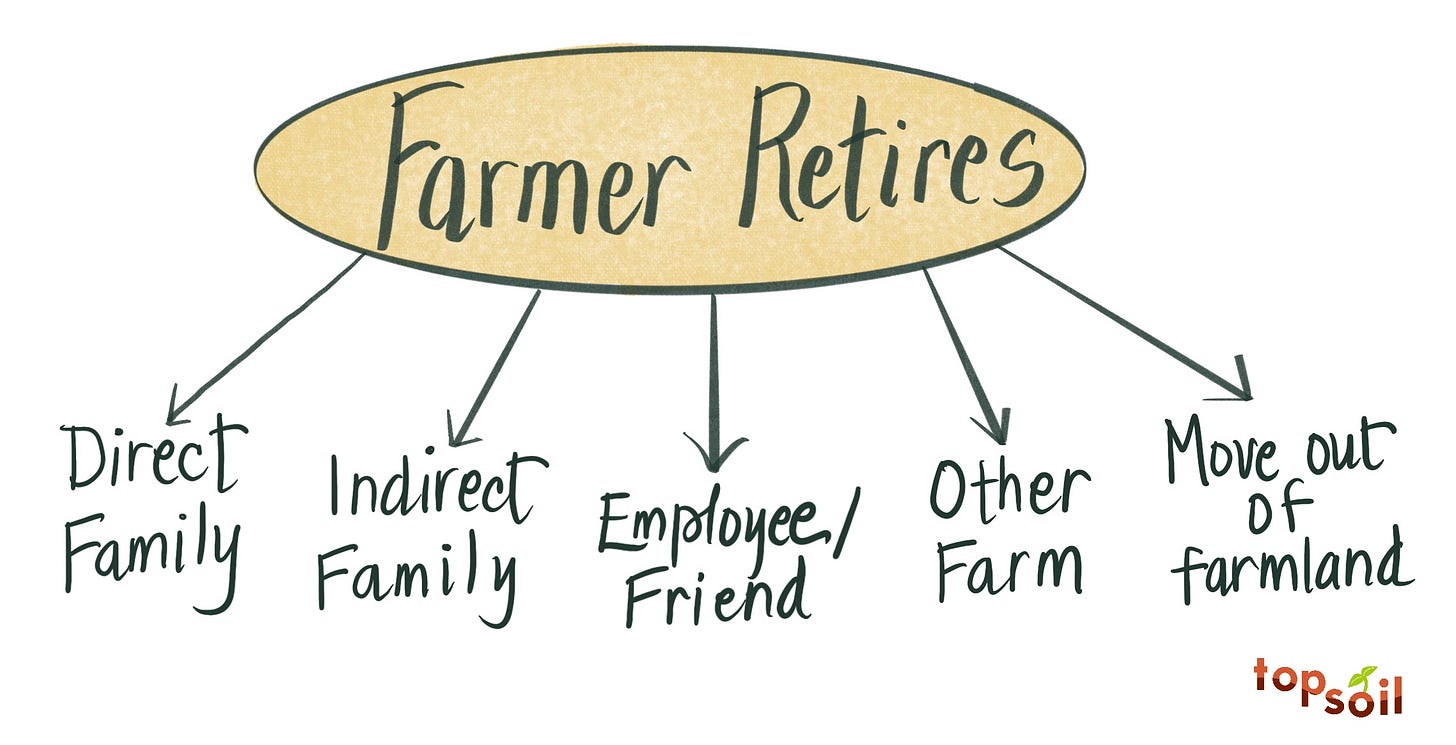

Lauren outlines five typical paths a farm may take:

In a 2012 survey of US farmers, 58% plan to give or sell the farm to a family member. This aligns with the ultimate goal for many farmers, which is to “uphold the value and legacy of the operation while giving the option to farm to future generations.”

Although it makes for a riveting plot in Bridgerton, “it’s not necessarily the case anymore that farms only pass from father to son or son-in-law.” Good news for anyone who’s not the eldest boy!

Farms may also pass to an indirect family member. Lauren explains, “Perhaps they don't have kids, or their kids aren't interested in farming, but they have a niece or nephew who is.”

Farming families often have deep ties with their employees and within their communities. In some cases, a farm will be sold to an employee of the farm, a friend, or a close acquaintance. Alternatively, other nearby farms are often on the lookout to pick up additional acres through private sale or at auction.

And in some cases, farmland will be developed for non-farming purposes, such as housing, business parks, strip malls or even wildlife refuges.

More than just assets

To pass on a farm, farmers can’t simply write a will, file it away, and call it a day. Lauren shares, “there is a big cloud of activity and nuance surrounding farm succession planning that entails more than simply asset handoff.”

Assets, primarily farmland, get the majority of airtime when talking about succession planning. And for good reason — farmland accounts for 83% of the balance sheet of a typical farm in the US (the remaining ~17% being equipment, vehicles, machinery, and inventory of inputs and grain).

However, there’s much more to a successful succession plan than just the physical assets. Below are other activities that a succession plan may also include:

Financial management: Developing tax and investment strategy, organizing financial records, and risk management

Operational management: Documenting processes and policies across the operation, creating agronomic plans and records, determining roles and responsibilities

Emotional management: Aligning on organizational values and long-term vision, strengthening relationships, and setting expectations

Of course, succession planning looks different for every farm, if it happens at all. Fewer than 20% of farms actually have their succession plans written down.

“It makes me think about the Rockefellers and the Vanderbilts,” Lauren tells me. “They were two of the wealthiest families in the country at one point. However, only the Rockefellers maintain their vast wealth to this day. The key difference is that the Rockefellers had a more comprehensive succession plan in place. They not only made use of irrevocable trusts to protect their assets and minimize estate taxes, but critically, they also created a family constitution in which family values and expectations were outlined. This is how the Rockefellers maintained their legacy for generations, as opposed to the Vanderbilts who squandered the opportunity.”

So how can farms get Rockefeller-like results in their succession planning?

At the highest level, farms must:

1) have a plan;

2) communicate that plan; and

3) revisit the plan regularly to make sure the plan stays up-to-date.

Lauren acknowledges that “no one wants to talk about, ‘when I kick the bucket one day.’” However, developing a succession plan is a “moment in time where you can analyze your purpose and reason for being in business. It’s a pivotal moment to know if you’re still driving towards the same north star generationally.”

Take a second to let that sink in. Farmers are not only thinking about next season or next year – through succession planning, they are making decisions that span generations.

For anyone who thinks that farmers can simply split the farm in equal slices of pie and hand it over to the next generation, think again. Lauren walked me through the concept of “equal versus equitable.”

Imagine the scenario below. A retiring farmer has a bundle of assets: land, buildings, cash, equipment, and inventory. He has two adult children – one who wants to continue to farm, and one who does not:

Now let’s see what it would look like if the retiring farmer split up his assets equally:

Both kids have the exact same distribution. This signs them up for constant back-and-forth negotiating about rent, purchases, and decisions on managing the farm, even though only one kid wanted to be involved in farming in the first place. This is not a recipe for sibling harmony. Lauren summarizes: “When you think about dividing up assets, farms that split up assets equally are the least successful in transitioning generations.”

In contrast, now let’s look at what an equitable distribution could look like.

The kid who wants to farm will control all of the assets she needs to manage the farm operation. She may have to rent some land from her sibling, but at least they will not need to negotiate equipment leases and other day-to-day management decisions. The non-farming kid may ultimately receive a smaller dollar amount, but will have more freedom to do as he pleases since assets like cash are more liquid.

There is no easy button when it comes to succession planning. As a result, a whole industry of specialists is popping up to help farmers through this process. Lauren notes that this mirrors the increasing professionalization of farms themselves. “I do not think my great-great-grandpa hired a human resources consultant,” but now, there are specialists who cover the spectrum from hardcore financial engineering to essentially “group therapy.”

Death and taxes

Farms have been changing hands in families for at least 3,500 years. Rules of land inheritance were literally written in stone at the dawn of civilization.

So you may be wondering, “Why is this important now?”

As we head into 2025, succession planning is becoming front and center in many farmers' minds for a few reasons.

First, nearly 40% of farmers are over 65 years of age. Even if they aren’t ready to retire quite yet, they are getting well into their “40 seasons” and can begin to consider their legacy.

The second reason, and one that makes this conversation urgent for some farming families, is quite simply: tax. Particularly, the potent combination of estate tax and all-time high land prices.

In the US, when you die, Uncle Sam claims a share of your assets above a certain threshold. In 2024, that number is around $13 million. In 2026, that threshold will be cut in half, to around $7 million.

Now I’m not a tax advisor, but let’s play this through with an example. Imagine you’ve got a 1,000 acre farm in Iowa. With the average land price around $10,000/acre, your land is worth about $10 million. Assuming your land makes up about 80% of the farm’s assets, that brings you up to an estate of $12.5 million.

If you happen to croak in 2024, your heirs will not pay a dime in estate tax. However, in 2026, if you don’t take any action, your heirs would pay taxes on $5.5 million, with tax rates from 18% to 40%. Your tax bill would be over $2.1 million.

This multi-million dollar difference is compelling many farmers to pull together succession plans and take steps to minimize their tax bill before 2026.

Ripple effects beyond the farm gate

It is estimated that up to 40% of the farmland in the US (370 million acres) could change hands in the next two decades. What might that mean for agriculture more broadly?

Lauren summarizes, “the farms that are good at succession planning will consume the farms that are bad at it.” There will be fewer, larger farms. In a word: consolidation.

Farm consolidation will reshape the broader agriculture ecosystem. Within farms, each member of the farm team will be more highly specialized as the farm covers more acres. If there are fewer farms, it follows that there will be fewer sales people, dealerships, and other agriculture businesses needed. Those who remain to serve farmers will need to up their game to stay competitive as decision-makers on the farm change over.

Additionally, there will likely be more landlords who are not farmers themselves. As of 2014, about one-third of US farmland is owned by “non-operator landlords” (those who own farmland but aren’t farmers). As Lauren points out above, not all those who inherit a farm actually want to become farmers. More than half of the non-operator landlords got their farmland through inheritance:

Of course, non-operator landlords are not all one and the same with identical goals and preferences. However, if more farmland is managed at a distance, there may be a broader diversity of requirements to lease certain parcels of land. Farmers may have to spend more time reporting out to absentee landlords.

As farmers represent about 1% of the US population, Lauren reflects on this moment in agriculture: “This is an opportunity that fewer and fewer people get to experience, so it's a gift to even be able to give the decision to continue to the next generation.”

Topsoil is handcrafted just for you by Ariel Patton. Immense gratitude to Lauren Riensche for sharing her wit, wisdom, and deep expertise. Complete sources can be found here. All views expressed and any errors in this newsletter are my own.

How did you feel about this monthly edition of Topsoil? Click below to let me know!

That lowered tax threshold is brutal.

Well done. Note that even the equitable distribution approach requires detailed planning. For example, will K1 be given the right - per a lease- to lease K2s land at a reasonable rent? If a reasonable rent cannot be agreed upon is there a mechanism to break the deadlock. Will K1 have a right of first refusal on K2s land perhaps with seller financing? There are always details and what ifs to think through and address. You are 100% correct. The plan needs to be reviewed and discussed no less than annually.

TFD